On Spatial Computing, Metaverse, the Terms Left Behind and Ideas Renewed

As computer networking, graphical user interfaces, and games entered the mainstream in the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a rash of terms and ideas put forward to describe what we were doing, would soon do, and might eventually do.

In 1981, the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard coined the term “hyperreality” in his prophetic treatise Simulacra and Simulation. As Jacobin’s Ryan Zickgraf wrote in 2021, “hyperreality is where reality and simulation are so seamlessly blended together that there’s no clear distinction between worlds,” a conclusion that many considered frightening (though also farfetched) at the time, “[but] ultimately, [Baudrillard] speculated, the difference wouldn’t matter because people would derive more meaning and value from the simulated world anyway” (Many parents will say their Roblox bills prove hyperreality has been here for years). That same year, mathematician and computer scientist Vernor Vinge released his sci-fi novella, True Names, which is considered one of the first popular depictions of cyberspace, transhumanism, and fully-immersive virtual reality (“The Other Plane”). Vinge imagined that in the "Other Plane," users would represent themselves under new identities, copy versions of themselves into largely autonomous AI replicants, and that as their physical bodies decline, they might transfer more of themselves into cyberspace so that, as one character says, "when this body dies, I will still be, and you can still talk to me".

A year after the publication of Simulacra and Simulation and True Names, novelist William Gibson introduced mainstream audiences to the term “cyberspace” in his short story Burning Chrome, which was then reimagined as the 1984 novel Neuromancer. Gibson described cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation,” and referred to its visual abstraction as the “Matrix,” which was “a graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data.” (In 1991, Gibson was asked about the influence of Baudrillard and hyperreality on Neuromancer, but replied only that Baudrillard was “a cool science fiction writer.”)

In between Burning Chrome and Neuromancer, the Walt Disney Company released the 1982 (family-focused) feature film Tron, written by Steven Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird, in which the “Cyberspace Matrix” was dubbed the “Grid.” Not only were the film’s ideas ahead of their time, the technology was, too — the Academy for Motion Picture Arts and Sciences reportedly disqualified the film from competing for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects because using computers to generate visual effects was cheating.

While Tron was in theaters, Damien Borderick’s sci-fi novel Judas Mandala was published, and with it, the first known usage of “virtual reality,” which, according to Borderick, did not require goggles or gloves to experience (direct integration into human consciousness was the recommended option). The following year, Myron Krueger coined the term “artificial reality” in his book of the same name, which covered of his 16-year effort to construct digital environments that humans could interact with in real time in response to bodily motions and without the use of goggles or gloves. One such example was “Videoplace,” a technology that tracked a user’s movements through external cameras and reproduced them on a digital silhouette on a screen. In 1983, Bruce Bethe’s short story “Cyberpunk” was also published, with the term later repurposed to describe the subgenre of fiction that “‘combined lowlife and high tech’ while featuring futuristic technological and scientific achievements, such as artificial intelligence and cyberware, juxtaposed with societal collapse, dystopia or decay (Burning Chrome and Neuromancer have since been designated prototypical cyberpunk novels). In his short, Bethe describes a future in which the the young exploit their technical sophistication (often to illegal ends such as hacking and digital vandalism) as a form of rebellion against societal norms and authorities.

During a 1988 episode of Star Trek, series creator Gene Roddenberry introduced the “Holodeck,” which went on to become one of the franchise’s most well-known concepts. The Holodeck itself was doubtless inspired by the 1935 Ray Bradbury short story The Veldt, which centered around an A.I.-powered virtual reality nursery that was never given a precise name (though a 1974 episode of the animated Star Trek: The Next Generation featured a “recreation room” that most viewers would now liken to the Holodeck).

In 1989, Neal Stephenson created a graphic novel concept that later became 1992’s Snow Crash, which effectively popularized the term avatar and coined the “Metaverse”, with many visionary founders attempting to build it in name over the ensuing decades. In 1990, Boeing researchers Thomas Caudell and David Mizell coined “augmented reality,” and the following year, Yale computer scientist and professor David Gelernter coined the term “mirror worlds.” By 1992 or 1993, Robert Jacobson, who co-founded the Human Interface Lab at the University of Washington alongside one of the “godfathers of VR,” Tom Furness, had established the term “spatial computing” and put it to commercial use.

By the mid-1990s, entrepreneurs, journalists, and researchers were using many different terms — and as these terms bounced between nonfiction and fiction, from lab to lab, and from technology to technology, they often ended up getting reimagined yet again, if not perverted or overlapped over one another. In 1998, University of Michigan researcher Michael Grieves introduced the concept of “digital twins,” which largely supplanted mirror worlds (it benefited, perhaps, from the growing popularity of the word “digital”). Whereas Gibson’s cyberspace was “consensual” and eagerly embraced, the 1999 film The Matrix reimagined the eponymous technology as an unwitting prison for the mind. In the Wachowskis’ original shooting script, Morpheus, having recently “awakened” the protagonist Neo from the Matrix, explains that “as in Baudrillard’s vision, your whole life has been spent inside the map, not the territory.” The line did not make the final cut, though the film retains a shot in which Neo picks up a copy of Simulacra and Simulation that has been hollowed out to hide his hard disk hacks from the fuzz. The Wachowskis tried to involve Baudrillard in their film, but he declined and later described the film as a misread of his ideas, giving this “hollowed out” reference an unintentional meaning.

Popular Mechanics, 1995

Around this time, the term “virtual reality” had come to mean a headset that enabled a user to interact with a virtual world using their head and/or eye movement, though neither Kreuger nor Borderick had ever intended such a requirement. Yes, there was a certain sense to the conflation — most people will say a headset increases their sense of immersion — but a headset is an input device, not a virtual environment or “reality” in and of itself. Nevertheless, this popular understanding of VR stuck due to its usage by institutions such as NASA and companies like Nintendo (even though NASA’s Project VIEW, pictured at the start of this essay, could display an “artificial computer-generated environment or a real environment relayed from remote video cameras,” and the Virtual Boy was just in the form factor of a headset and could not display real 3D or track hand/body movements).

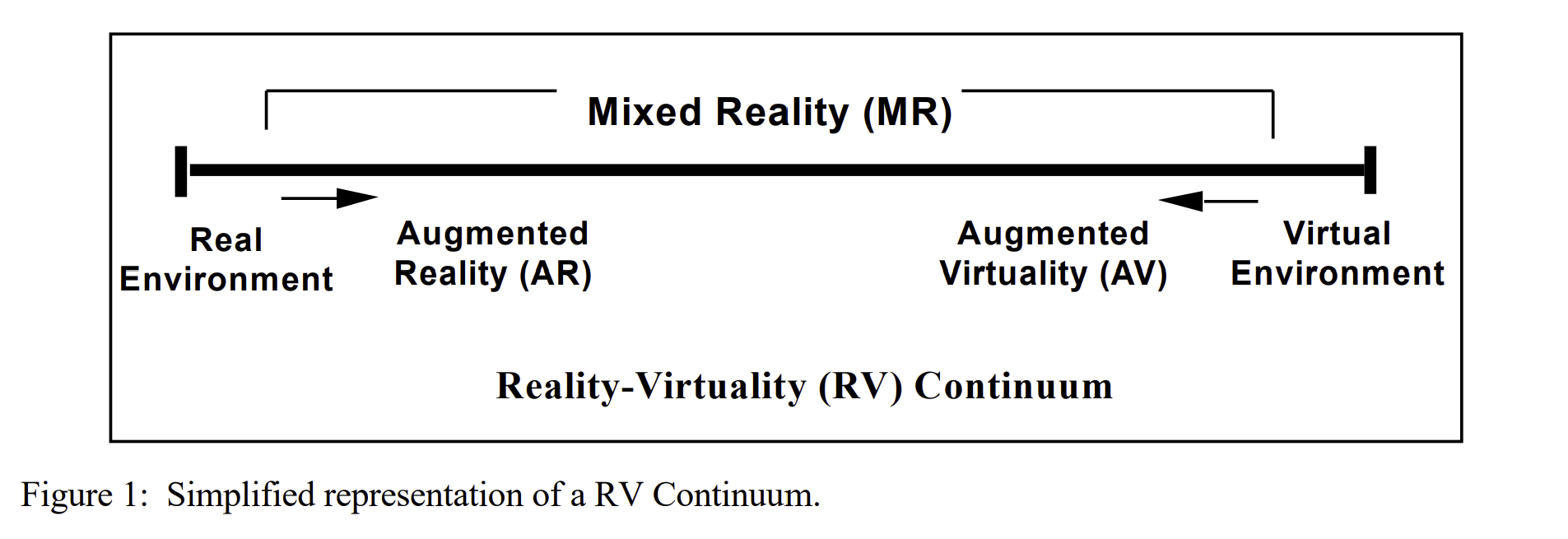

By the end of the decade, a number of efforts had been made to establish taxonomies in published literature. One of the more notable examples is Milgram and Kishino’s Reality-Virtuality Continuum in 1994. And though largely intuitive, it was not widely embraced and even its central concept of “virtuality” is not really used.

A Term By Any Other Name Could Have Been Any Other Name And Might Still Become One

Even if Published Works were able to enshrine Definitive Definitions, our language would have evolved. The terms of the 1980s and 1990s were intended to help describe or encapsulate the or a techno-future of humankind, but it did so based on what was known or seemed likely at the time or, a separate concern, what served narrative purposes. In 2017, as the ideas of the Metaverse began to bubble back up into publish consciousness for a third time, Neal Stephenson warned that Snow Crash was “just me making shit up” at a time that was “pre-Internet as we know it, pre-Worldwide Web.” The emergence and maturation of these latter technologies necessarily altered how we thought about existing terms, and sometimes we leave the old terms behind. In fact, while titles such as Neuromancer and Snow Crash sought to visualize digital information and networks, most of the time since these novels were published have involved us shedding these sorts of ideas.

We no longer say “Information Superhighway '' or “World Wide Web,” neither of which is a particularly accurate description of the respective underlying technologies. The “web” and “surfing” have lingered, but these two terms are likely doomed in the same way the “floppy-disk symbol” for “save” is being phased out because every year, another 100 million new computer users have no idea why it means save, let alone what it literally represented. “Web addresses'' still have “www.” but users need not ever type it. “Surfing” took off as a convenient way to describe the ease with which a consumer could change TV channels or websites (this is sometimes traced to Marshall McLuhan’s influential 1962 book “The Gutenberg Galaxy,” which rhapsodized about a world in which “Heidegger surf-boards along on the electronic wave as triumphantly as Descartes rode the mechanical wave”). Yet most consumers don’t watch TV channels anymore; they stream distinct streaming services and clickable content tiles. An increasing share of internet usage is via apps — not browsers — which are infrequently deep-linked and certainly lack the wave-link integration of the World Wide Web.

There was a time in which Apple’s interfaces were rife with skeuomorphism — the iOS games center was a green felt casino table, the bookstore resided on a wooden bookshelf, the calendar app featured mock stitching, the notes app was yellow with lines and margin rulers, etc. — but eventually, we no longer needed such cues to use these applications correctly. Indeed, we no longer even use the term “graphical user interface” and just say “user interface” or “interface,” or, more abstractly, user experience. The “graphics'' part is now assumed.

The recurring problem with skeuomorphism is that it often complicates a GUI without making it more functional or intuitive. Its initial prevalence stemmed from its use as a design crutch as developers digitized tangible 3D products into 2D ones with no physical components and which sometimes offered unique capabilities, too. In recent years, however, technology has begun to catch up to our largely pre-Internet imaginations of how we would interact with the Internet (or something like it): in 3D. Accordingly, we are seeing a revival of some of the terms of the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2023, Apple took on the 1993-ish term “spatial computing.” Two years earlier, Tencent chose “hyper digital reality,” and five months after that, Facebook invoked the “Metaverse” to describe its future. Facebook’s usage was the most prominent — it was, after all, the seventh largest company in the world, the youngest company in the top 25, one of the most successful examples of a company pivoting from one era (PC) to another (mobile), and it was changing its name to Meta. Yet Facebook was not alone in its selection of “Metaverse.” In 2021, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and Nvidia founder/CEO Jensen Huang began extolling the enormous importance of the impending Metaverse (Huang in November: “The Metaverse is going to be a new economy that is larger than our current economy . . . much, much bigger than the physical world”). A year earlier, Roblox, Unity, and Epic Games had each begun to publicly describe their businesses as building the Metaverse. And Epic CEO Tim Sweeney, for that matter, had been talking publicly about the Metaverse since at least 2016 and working toward it since the 1990s, while Facebook had been internally organized around that mission since at least 2018 (A memo to the Board of Directors from that year warned “The Metaverse is ours to lose" and “If delivering the Metaverse we set out to build doesn’t scare the living hell out of us, then it is not the Metaverse we should be building.”)

Académie Metaversál

Why the term Metaverse took hold, specifically, is an unknowable question. “Cyberspace” seems to have been left behind — probably because it was too commonly used to skeuomorphically describe where online “things” “resided” in the 1990s — while the “Matrix” was likely impaired by the blockbuster success of the film of the same name. Maybe the “Grid” was too similar to other already-popular terms such as the “power grid.” Virtual reality never really went away, which is problem number one, but it was also too firmly associated with hardware, problem two, and those products were typically considered flops and “uncool.” Three strikes. VR-adjacent terms, such as AR, the newer MR, and newest XR, brought their own taxonomy problems and, in an inversion of VR’s problem, lacked products that would have given consumers an intuitive understanding of one versus another.

Under classical (though still simplified) definitions, augmented reality refers to interactive, digitally rendered information that is overlaid on top of the “real world” and refers directly to the real world. The most famous “AR” experience is Pokémon Go, but for years (including at the height of its popularity) it was not really “AR.” Instead, what users saw was essentially just a 2D image of a Pokémon through the passthrough video feed of their smartphone camera — not altogether unlike placing a Pikachu sticker on your screen (though in that instance, it would have a few different postures, might jump, etc.). If the user tilted their phone up, the Pokémon wouldn’t “stay” where it “was” in the background but instead follow wherever the camera pointed. In the flick of a wrist, a flying Pokémon might be incomprehensibly underground (and not know it was), or a flightless Pokémon might suddenly find itself soaring in the sky (which would not prevent it from stamping the nonexistent ground underneath it). Many users simply turned off “AR” in order to preserve battery, as there was scarcely any benefit to the functionality. Eventually, Niantic added context that empowered Pokemon to “anchor” in position and in appropriate ways, such as enabling them to hide behind real-world objects (a tree); should the user throw a virtual pokeball at the hiding creature, it would bounce off the obstruction. The users could even walk around a given Pokémon to see them from another angle (which also demonstrated that the model was truly 3D).

In recent years, the term mixed reality has gained favor. In contrast to AR, MR explicitly calls for the real and physical world to be intermixed — and richly so. Imagine, as an example, not just “anchoring” a virtual TV screen to your living room wall but playing racquetball against it (complete with virtual projectiles ricocheting across your furniture, if you so chose). Yet exactly where AR stops and MR begins is bound to be fuzzy. Magic Leap described itself as an AR company but would now be described as an MR company (many former employees report that their work there was primarily spatial, though it’s also worth stressing that Stephenson served as Chief Futurist for close to decade, too!). Regardless, note that in the case of AR and MR, we are talking about the technology and experience, not the device — unlike VR.

Many in the tech community hate the term extended reality (XR) because it’s a catchall that covers everything and thus barely means anything specific. Worse still, some folks take XR to mean everything other than AR/VR/MR, such as “XR projectors” that enable the real world to assume a touchable interface.

The flaws, narrowness, and technical orientation of VR/AR/MR/XR are, presumably, a partial explanation for Zuckerberg and others’ preference for “metaverse” in the first place. The word is a portmanteau of “meta,” the Greek term for “above” or “greater than,” and the backformation of “-verse,” as in “universe.” The Metaverse thus spans and connects all universes — real and non-real — and the many technologies that comprise our area used to experience them. This is the perspective shared by Sweeney, Huang, and Nadella, as well as Zuckerberg, who, in the months leading up to the name change, said plainly the Metaverse “isn’t just virtual reality. It’s going to be accessible across all of our different computing platforms; VR and AR, but also PC, and also mobile devices and game consoles.”

Though Big Tech executives don’t mean VR when they say Metaverse, that’s what the term means to the average person (or more limiting still, the Metaverse means a cartoon playground in VR). This is probably because at the time of Facebook’s name change, most of its Metaverse-focused hardware were VR-only, and the company’s signature social platform, Horizon Worlds, was also VR-only and cartoonish. Another problem is that, for the most part Stephenson did mean VR when he wrote Snow Crash, but as with the executives who largely worship his books, no longer does:

“The assumption that the Metaverse is primarily an AR/VR thing isn’t crazy. In my book, it’s all VR. And I worked for an AR company [Magic Leap] — one of several that are putting billions of dollars into building headsets. But I didn’t see video games coming when I wrote Snow Crash. . . . Thanks to games, billions of people are now comfortable navigating 3D environments on flat 2D screens. The UIs that they’ve mastered [keyboard and mouse for navigation and camera] are not what most science fiction writers would have predicted. But that’s how path dependency in tech works. We fluently navigate and interact with extremely rich 3D environments using keyboards that were designed for mechanical typewriters. Its steampunk made real. . . . My expectation is that a lot of Metaverse content will be built for screens (where the market is) while keeping options open for the future growth of affordable [AR/VR] headsets.”

- Neal Stephenson, June 8, 2022

As Meta’s product suite diversifies and its vision is realized, the public misperception may change, but at the same time, the company’s very success (or lack thereof) might also alter the word.

Not Who is On, But Who Is First

As early as 2022, it was obvious that many of the companies that had previously used the term Metaverse began to back away from it. The most likely cause was not its complexity, but it’s gluey association with Meta, whose name changed coincided with a precipitous (though essentially unrelated) fall in its share price. The term was also adjoined to crypto, which experienced its own free fall over the ensuing 18 months and was rife with entrepreneurs who used the indescribable “metaverse” buzzword as a sort of multi-trillion dollar plug that would justify their valuations.

In 2023, a Roblox developer told the boss, founder and CEO David Baszucki, "I have always thought of Roblox as largely a metaverse company. . . . Recently, I’ve become aware of a brand marketing push, I believe by your sports division, to distance yourselves from metaverse connotations. Can you please tell us about that?" Bazsucki replied, “I wouldn’t say that’s a distancing. We have evolved the terminology we’ve used. We’ve always used the term ‘human co-experience’ or ‘bringing people together.’ . . . We’ve never really used the term metaverse a lot, and I think going forward, we’ll probably always think of ourselves as a communication and connection platform.’ This is a bit absurd. At the time of Roblox’s October 2020 IPO filing, the term “Metaverse” had appeared in only 17 filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission since January 1, 2001. In its filing, Roblox used the term “Metaverse'' 16 times, writing that Roblox operated in a category sometimes known as the “metaverse” and that Roblox believed was “materializing,” with its “business plan [assuming] . . . the adoption of a metaverse.” During the company’s pre-IPO roadshow, Roblox’s Baszucki wrote an opinion piece as part of Wired magazine’s 2021 predictions column, titled “The Metaverse Is Coming,” in which he predicted that “billions would come to [Metaverse] platforms such as Roblox'' and that the “Metaverse is arguably as big a shift in online communication as the telephone or the internet.” Then, on the day of the company’s March 2021 IPO, Baszucki tweeted, “To all those who helped get us one step closer to fulfilling our vision of the #Metaverse-thank you. #RobloxIPO.”

Such a departure is understandable. In the span of only a few hours, a once obscure and somewhat malleable term became loaded and often “off brand” in a way that “Internet” or “mobile” never had. Suddenly, having a “metaverse” strategy could be interpreted as sharing (or rushing to catch-up to) Meta’s precise vision — or worse, the public misperception of it. The many “Metaverse companies” not focused on “virtual reality” were assumed to be.

In 2021, Niantic, the makers of the augmented reality/location-based entertainment game Pokémon Go, partly rebranded itself as as a “real-world Metaverse” company, with the founder also writing an essay entitled “The Metaverse Is a Dystopian Nightmare. Let’s Build a Better Reality” (a real-world dystopian nightmare seems rather worse than a fictious one, but ¯\_(ツ)_/¯). A year later, Niantic was still using the term “real-world Metaverse” to summarize its vision and attract talent (pictured below from the SVP of Engineering). But by 2024, Niantic had mostly reverted to AR (MR is starting to seep into its company copy), though at the bottom of every page, Niantic writes “Come build with us: The real-world metaverse requires as many perspectives as possible. Let’s build it together” while pointing developers to its Lightship SDK and potential hires to its career page.

Eventually, Jensen Huang of Nvidia, began to refocus his talking points on the Nvidia-trademarked term Omniverse, which refers to their real-time collaboration and simulation platform. Microsoft always used the term “industrial metaverse” — which intuitively separates itself from Meta’s cartoonish VR game world — but now, it mostly just talks about its “Mesh” products or the integration of Office software into VR/MR devices such as the Quest or Vision Pro.

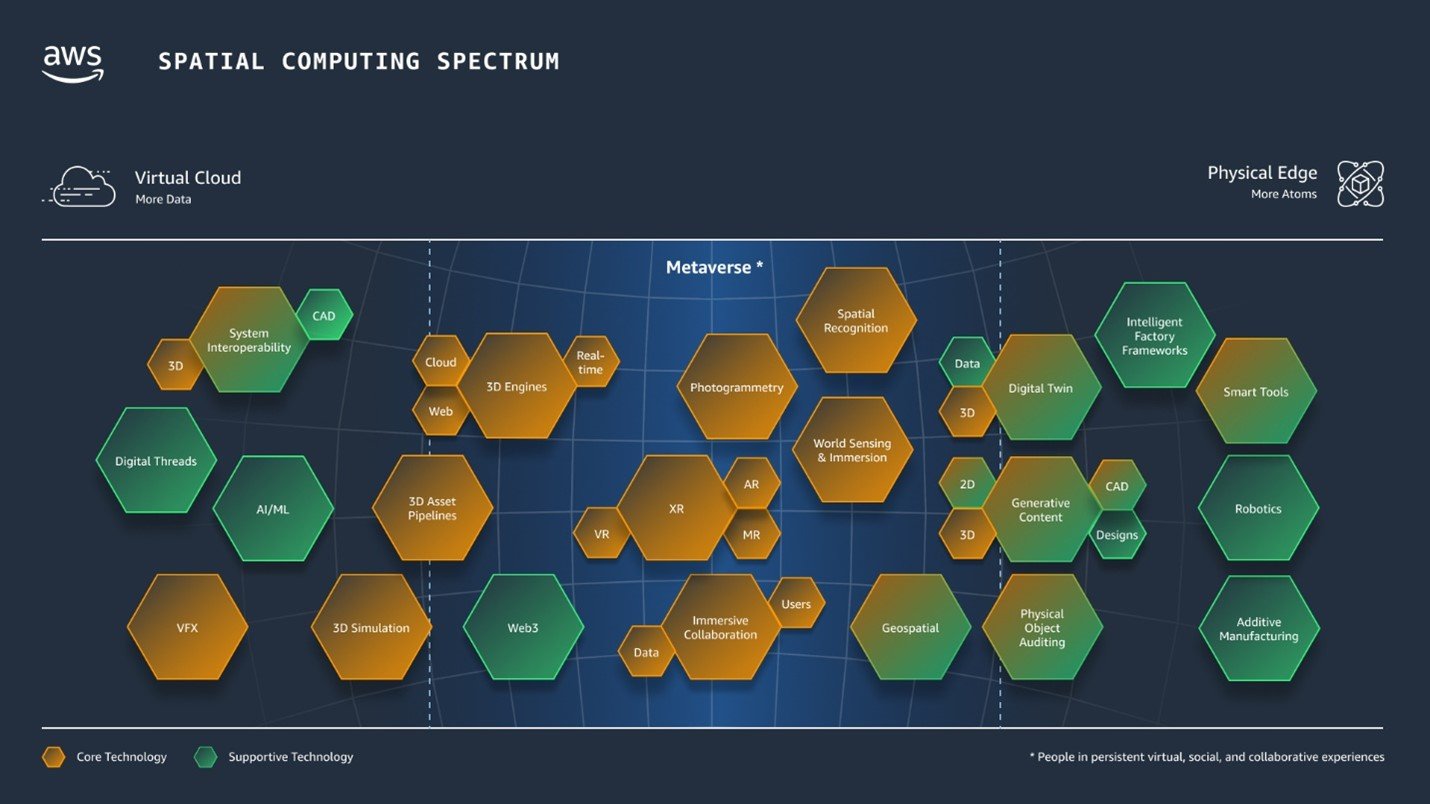

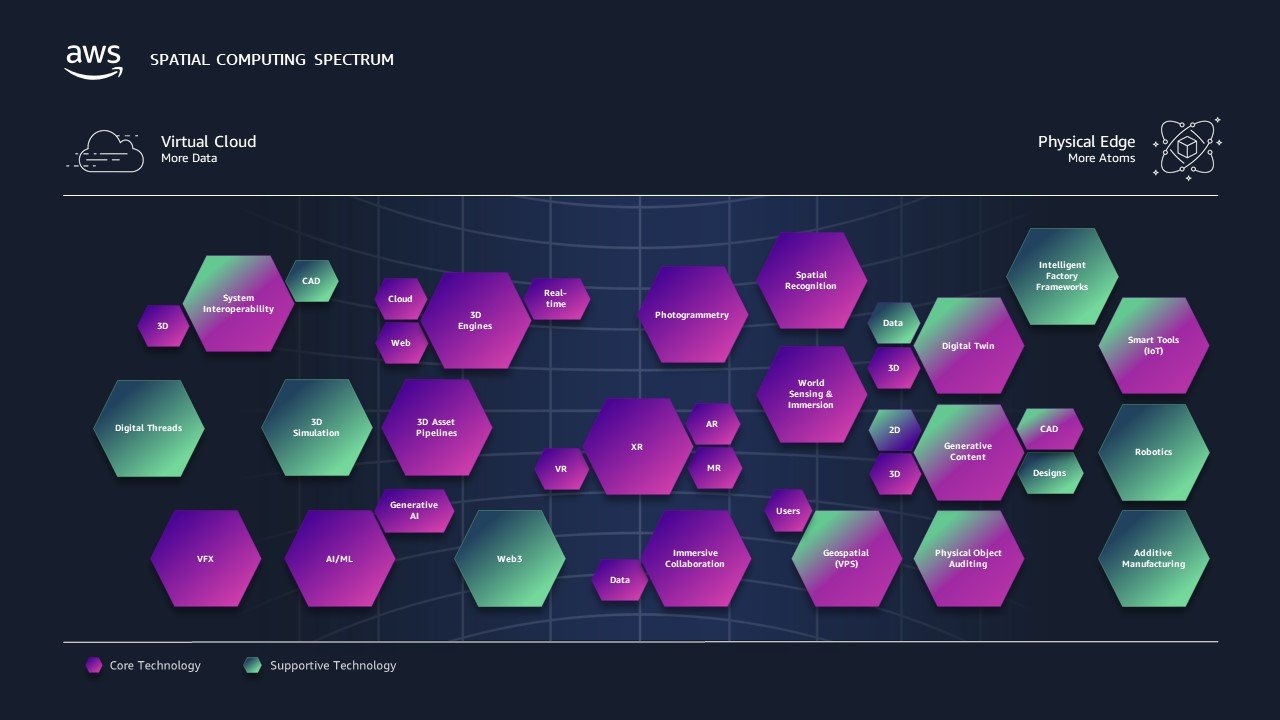

In early 2023, Amazon AWS’s “Spatial Computing Spectrum” was centered around the “Metaverse.” As a company blogpost put it:

“[We] view the metaverse as a combination of a number of technologies roughly in the middle of this spectrum . . . definitions in this space are very fluid, and many groups have yet to arrive at a consensus definition for metaverse. . . . At some conferences people jokingly say that they do not want to say the word ‘metaverse’ out loud since there is so much controversy and ambiguity around it. While it may be difficult to define the metaverse, I think we all can agree on at least some of the technologies that will power it; those are referenced in our Spatial Computing Spectrum diagram.”

By the end of 2023, this diagram was still being used, but the term “Metaverse” had been entirely memory-holed. The only lingering evidence was the filename, which changed from “AWS-Spatial-Computing-Spectrum.jpg” to “Spatial-and-Automation-GenAI-Diagrams_no-metaverse.jpg”

Many professional services firms have followed similar paths to Amazon’s graphical revisionism — those who were formerly Metaverse experts are now a spatial or immersive executives, and in fact, LinkedIn suggests that has always been their title and focus. Again, there’s nothing wrong with this, but the flight from Metaverse is real and usually just in name. Note that while Epic Games and Meta have stuck to the term, Zuckerberg is continually working to convince investors and members of the press that his commitment to it endures, too. The argument he has “pivoted" away boggles my mind — one need only look at the consistent year-over-year increases in Reality Labs spending and losses to validate his commitment, especially given other areas of the business are cutting back — but the very expectation he would shift away from the term is telling. And when Disney announced its partnership with Epic Games, the terminology used was quite conspicuous, as well as the absence of the M-Word. According to Disney, the two companies were building “an expansive and open games and entertainment universe connected to Fortnite,” while Tim Sweeney said “a “persistent, open and interoperable ecosystem that will bring together the Disney and Fortnite communities.”

A-V-P

All of this brings us to the Vision Pro, Apple’s “spatial computer,” which, the company has said, will start the “era of spatial computing.” The company’s submission guidelines for developers require all apps to use the term “spatial computing” and never AR, VR, MR, XR. This struck many developers as absurd — especially given that Apple was simultaneously buying Google Search keywords for “AR” and “VR” to promote its “spatial computer” and the company has refused to define what, exactly, “spatial computing” is. A clue comes from Tim Cook, who stays on message with “spatial” today, but historical word choices are clear and consistent. In 2016, just as development of the Vision Pro was kicking off, he predicted that “a significant portion of the population . . . will have AR experiences every day, almost like eating three meals a day. It will become that much a part of you. . . . VR I think is not going to be that big, compared to AR. I’m not saying it’s not important, it is important.” And then only nine months before the June 2023 reveal of the Vision Pro, Cook was recorded saying, “I’m super excited about augmented reality. Because I think that we’ve had a great conversation here today, but if we could augment that with something from the virtual world, it would have arguably been even better. So I think that if you, and this will happen clearly not too long from now, if you look back at a point in time, you know, zoom out to the future and look back, you’ll wonder how you led your life without augmented reality. Just like today, we wonder, how did people like me grow up without the internet.”

We also know that Apple wasn’t quite sure what to call the Vision Pro or its technology, either. In the last few weeks before the device was unveiled, there was extensive reporting around Apple registering trademarks such as “Reality Pro,” “RealityOS,” and “xrOS.” Even documentation and press videos released on June 6, 2023, included the term “xrOS,” which was also found in open-source code released by Apple in the months leading up to that date

More important than the specific baggage inherited from a given term is the desire to have none at all. Apple never called the iPhone a smartphone but instead “a revolutionary mobile phone” that combined a “widescreen iPod and an internet communicator.” It still became the defining smartphone. The Apple Watch, unsurprisingly, was not a “smartwatch” but “a revolutionary product that can enrich people’s lives” and “Apple’s Most Personal Device Ever.” Back in 2001, Apple occasionally included the term “MP3 player” in its marketing copy for the iPod, but the company typically led with “a whole new category of digital music player” that “puts 1,000 songs in your pocket.” Apple is reliable in that it doesn’t like to be first to a category, yet largely pretends that category did not exist before them. And in many ways — and to many consumers — the category didn’t. It’s easy to find headlines which suggest Apple doesn’t believe in “The Metaverse,” but Cook has been forthright on the matter: "I always think it's important that people understand what something is,” he told the Dutch outlet Bright in September 2022. “And I'm really not sure the average person can tell you what the metaverse is."

From AM to FM

While it’s fair to say there are differences between the visions of the future presented by Meta and Apple, these differences appear larger than they appear because they are expressed through companies with different business models and priorities, customers and taste profiles (“style”), strengths and weaknesses, and perspectives on the “minimum viable product.”

Apple is a hardware company, and so it’s unsurprising they are focused on the hardware (a “spatial computer”) and what it can do that other devices cannot do or cannot do as well. Keep in mind that for nearly three decades, most of the time spent on Apple devices has been spent on software Apple did not make. Though Meta needs to make compelling hardware and sell consumers on that hardware, it’s typically more focused on the experiences that run on these devices, which explains its acquisition of multiple gaming studios and historical focus on gamers, it’s avatar-centric social networking functions, and suite of software for productivity, communications, and game-making. Again, this makes sense. Facebook’s network of apps are a, if not the, primary thing that many internet users do on their computers — computers that Facebook doesn’t make. For similar reasons, Apple is more focused on “the real world” — which its devices live in and are used to interact with – than Meta, which is a digital forum. As a free service, Facebook has been able to reach 3.2 billion people on a daily basis out of the 4.6 billion total Internet users outside of China. Apple has 1.5 billion including China. Some of Facebook’s users generate only a few cents a year; nearly all of Apple’s generate hundreds.

These differences manifest in the timing, price point, and construction of their HMDs (head-mounted displays). The most obvious difference is that Apple’s device is extraordinarily expensive. In many countries, the sales tax on the $3,500 Vision Pro will exceed the price of a new Quest 2 and is nearly that of a new Quest 3. Meta’s most expensive headset, its “Pro” model, is still 72% cheaper than the Vision Pro. This is a choice. One that has considerable implications on what a device can do, how it feels, and the like. Such a range isn’t unusual in consumer electronics — Apple’s cheapest iPad is $329, whereas its priciest model starts at $1,099 and finishes at $2,200 — but what matters here is that Apple doesn’t seem to believe it’s worth shipping a device that, at today’s component costs, is less than $3,500 a unit. That is, the “minimum viable headset” from Apple’s perspective is one with an 8K-combined display, 12 tracking cameras, low latency full color passthrough, automatic lens adjustments, and so on. Meta does not share this perspective, which is why they were able to come to market so much earlier, cheaper, and lighter. It also explains why Meta’s devices were, for years, limited only to VR, and why, even for the 2022 Quest Pro and Quest 3, MR is mostly a feature for an otherwise VR-centric device. For Apple, VR is a mode on its otherwise MR-focused device (though many reviewers have argued that it is, still, a VR device; it is notable that while the MR is robust, the device cannot really “understand” anything it sees).

The relative cost of Meta’s and Apple’s hardware also explains why the former has cartoonish avatars and the latter more realistic avatars based on Lidar scans of the user’s face. Meta is capable of much higher-fidelity avatars — as Zuckerberg demonstrated in an interview with Lex Fridman — but this would require devices of much greater power that would cost more and weigh more, and these avatars would not be compatible with the 25 million or so Quest devices that have already been sold.

As a social networking giant, Meta is obsessed with how it can maximize the size of its network. It also knows that high fidelity is not essential to virtual socializing - as Roblox’s 70MM daily users and 350 million monthly users demonstrates (note this is different from saying Meta’s visual aesthetic is good). What does matter is access. And Meta spends billions expanding it. By the end of 2024, the company is expected to have partial, complete, or de facto (i.e., capacity-based) ownership of 13% of global submarine cable infrastructure — more than 170,000 kilometers of cables in total, connecting nearly 33 countries across 47 connections, while reaching 36% of the global population (mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia).

Meta’s desire to expand the addressable market is also why its headsets are typically sold at a loss (which further constrains its build costs). The business model of Apple, formerly known as Apple Computer, literally does not allow for such discounts. Indeed, the company has a more than 46% positive margin on its hardware.

Regardless, the commonalities between Apple and Meta’s visions is clear when we look beyond current products and constraints, as in Meta’s “possibilities with the Metaverse” commercial from February of 2023, which looks eerily familiar to Apple’s own Vision Pro videos from June of that same year - inclusive of medical demos of knees and immersive classroom lessons featuring prehistorical animals brought to life. Corporate language is similar, too. “We live in a 3D world, but the content that we enjoy is flat,” Tim Cook told Vanity Fair in February 2024, with Apple.com saying that the device allows wearers to “remain connected to those around you” versus pulling up their phones. In July 2021, Zuckerberg told The Verge “We’re basically mediating our lives and our communication through these small, glowing rectangles. I think that that’s not really how people are made to interact…. People aren’t meant to navigate things in terms of a grid of apps. I think we interact much more naturally when we think about being present with other people.”

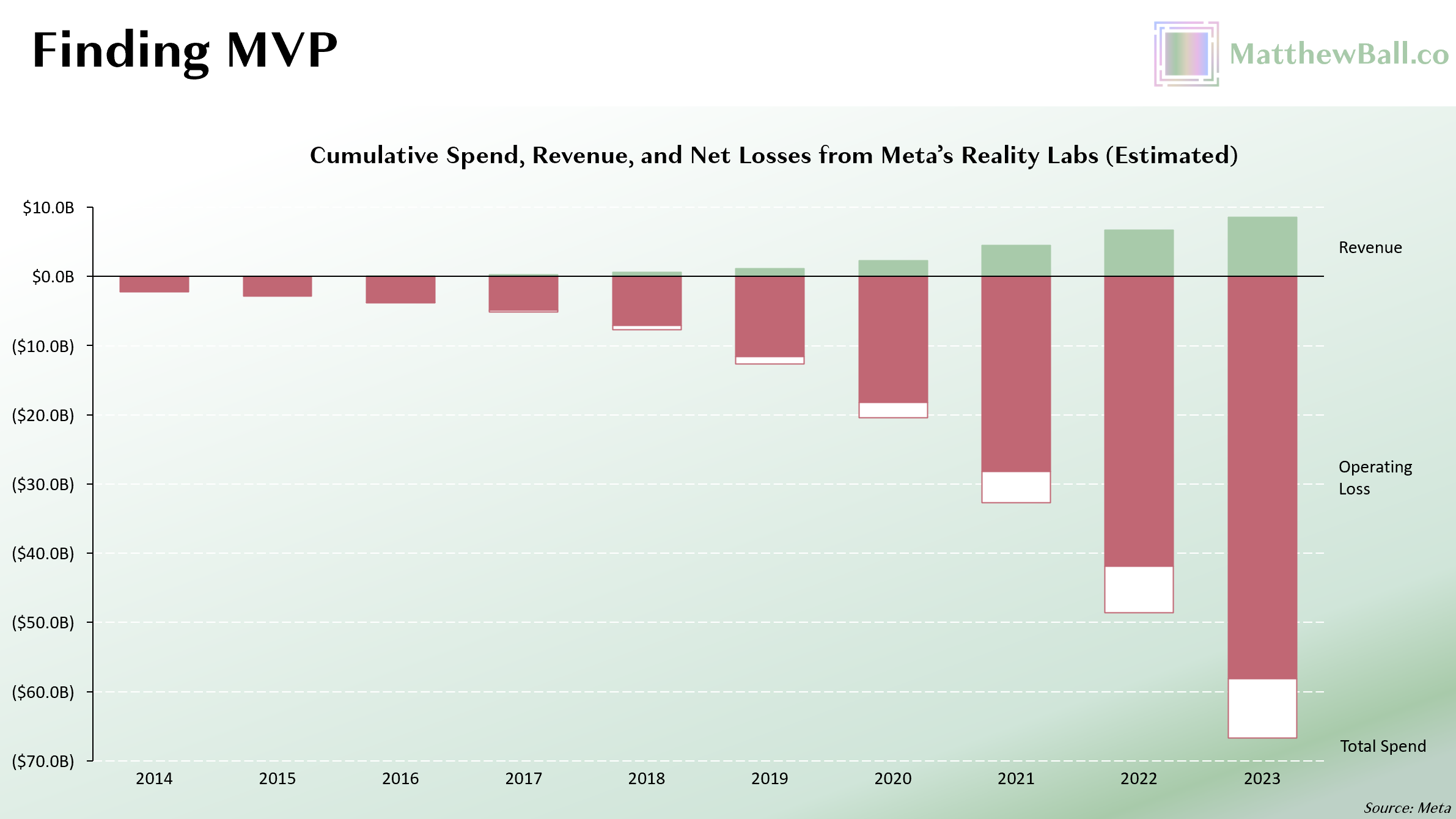

The sums invested by these two companies are remarkably similar, too. By my estimates, Meta has spent approximately $67B on its Reality Labs division since 2014 and through Q4 2023 ($58B net of revenue). This spend spans marketing, manufacturing, and device subsidies, as well as investments into software, R&D, and M&A, some of which relates to devices, technologies or experiences that have yet to be released (e.g. neural interfaces, electromyographic wristbands, AR glasses), with another portion relating to products Meta has since discontinued (Portal) or shuttered (smart watches).

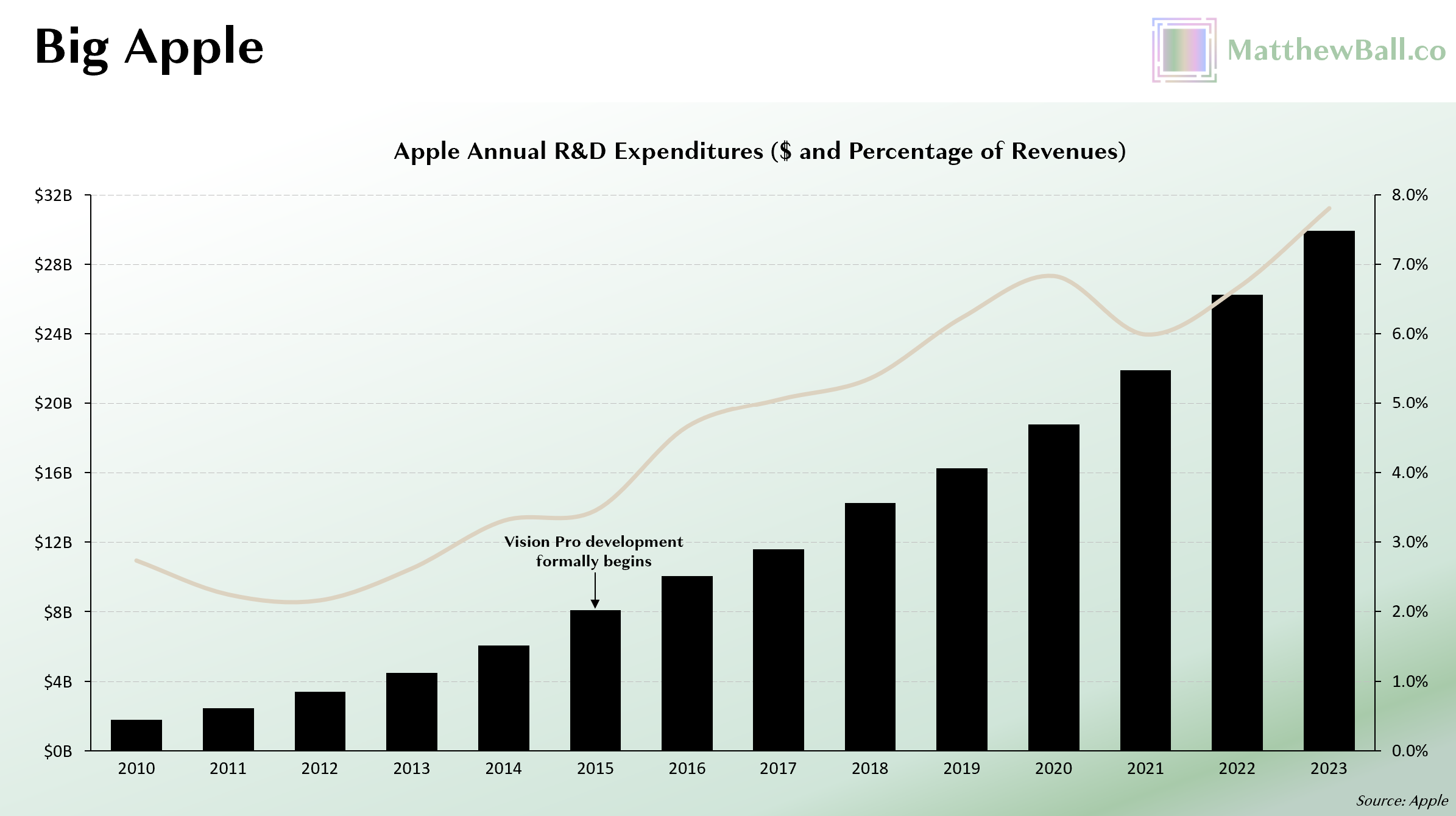

There is no way to know how much of Apple’s R&D spend relates to its XR headsets and the company never discloses (and argues it does not have) direct P&Ls for its products. Investments in Apple silicon technology, displays, production capability, et al, are widely repurposable. But when he unveiled the Vision Pro in June 2023, Apple CEO Tim Cook said the device counts more than 5,000 patents and was the “ the most advanced consumer electronics device ever created.” In the eight years since development of the device began, Apple has spent $149B in R&D and filed 20,000 total patents (many of which relate to the Vision Pro, but are not used by yet). No matter how you allocate that $149B to the Vision Pro, the product is a Very Large Number.

1980s / 2020s

At the start of this essay, I wrote “As computer networking, graphical user interfaces, and games entered the mainstream in the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a rash of terms and ideas put forward to describe what we were doing, would soon do, and might eventually do.” We sit in a similar position now as social gaming and HMDs, to a lesser extent crypto, and to a larger extent AI, all rise to prominence. There’s no authority to any one term, lots of baggage with some, and many rival mandates. But there is consensus.

Consensus that we are on the cusp of a new era in which the internet isn’t something we reach for, or that runs underground and is transmitted through the air. Instead, it will be all around us and we will be in it. That the world will represented by an infinite number of 3D simulations that are running in the buildings we walk through and the cars that drive by, which dynamically manage the traffic lights of our street and manage our checkouts as we leave a store, and which involves many objects that are not “real” in the sense they cannot be touched, yet nevertheless interacted with by millions each day. This future will feel very different from loading an app or webpage, but no one knows exactly what it will look like or how it will operate. All the same, many are convinced we’ll want (or need) new devices to help navigate this future - optical AR/MR glasses and passthrough AR/MR, sometimes just VR - plus AI that can “see,” understand, and help run the real and non-real, too.

Amazon CTO Werner Vogels in 2022

I liked the term Metaverse because it worked like the Internet, but for 3D. It wasn’t about a device or even computing at large, just as the Internet was not about PC nor the client-server model. The Metaverse is a vast and interconnected network of real-time 3D experiences. For passthrough or optical MR to scale, a “3D Internet” is required - which means overhauls to networking infrastructure and protocols, advances in computing infrastructure, and more. This is, perhaps the one final challenge with the term - it describes more of an end state than a transition. The Internet is not just faster, more popular, and more populated than in the 1990s, it’s literally larger - there are now more than 110,000 participating networks - but it wasn’t “incomplete” back then. The Metaverse is usually spoken about as something we one day reach, yet isn’t here today, and thus cannot be experienced. Spatial computing, though, well that’s been here since the day Snow Crash was published.

Matthew Ball (@ballmatthew)

Preorder “THE METAVERSE AND BUILDING THE SPATIAL INTERNET,” the fully revised and updated edition of my 2022 book, which was a national bestseller in the US, UK, Canada, and China, and selected as a Book of the Year by Amazon, The Guardian, FT China, The Economist Global Business Review, and ByteDance Toutiao.