Big Tech’s Biggest Bets (Or What It Takes to Build a Billion-User Platform)

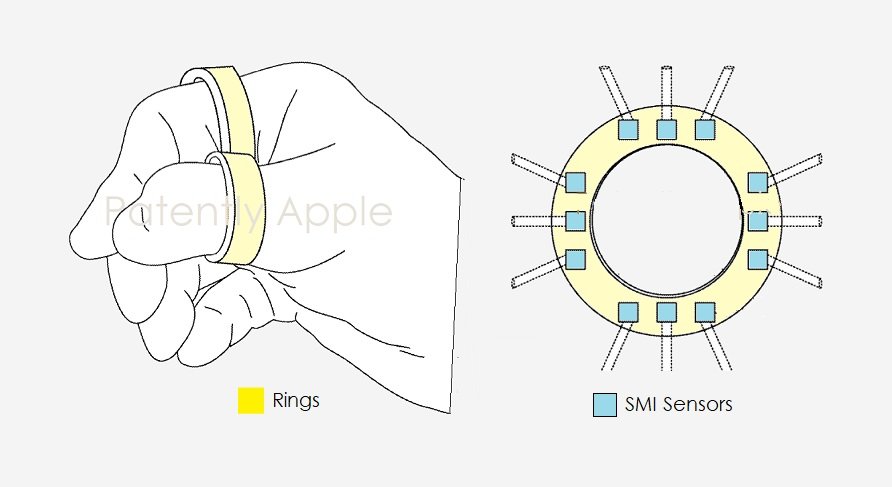

By my estimates, Meta has spent approximately $56B on its Reality Labs division since 2014 and through Q2 2023. This spend spans marketing, manufacturing, and device subsidies (most Quests are sold below-cost), as well as investments into software, R&D, and M&A, some of which relates to devices, technologies or experiences that have yet to be released (e.g. neural interfaces, electromyographic wristbands, AR glasses), with another portion relating to products Meta has since discontinued (Portal) or shuttered (smart watches).

Thus far, Reality Labs has generated about $7B in cumulative revenue against the above spend, producing a $49B life-to-date net loss for the division. The exact figures aren’t available, but we know the division was effectively formed in 2014 following the $2B acquisition of Oculus VR, and Meta has disclosed its spending from Q1 2019 through Q1 2023. Given these data points, the early years of the division are relatively easy to model and can be cross-referenced against sales records and various statements by Facebook throughout the decades. Revenues and expenses have been comparatively modest during that time, and thus assumption errors are less consequential. But even if we just use Meta’s disclosures, acquisition Oculus VR, and guidance for Q2 2023, the company is out at least $44.5B net. And this sum continues to grow.

2023 and 2024 should see Meta’s Reality Labs achieve new revenue highs. The Meta Quest 3, set to debut in October, boasts substantial improvements over 2020’s Quest 2 (+30% resolution, standardized 120 FPS, a mixed reality mode, a lighter and thinner form factor). It will also coincide with the launch of Roblox on the Meta Store, which is likely to become the platform’s most popular application (potentially orders of magnitude more popular than Meta’s VR-only Roblox competitor, Horizon Worlds). Although Apple’s forthcoming headset will create competitive pressures for Meta, which has heretofore enjoyed 90% market share of new device sales, but it will also produce a halo effect.

Apple is one of the most beloved companies in history, and its debut in the XR headset category will have the effect of legitimizing it while also helping consumers better understand its use cases and benefits—something Apple has done more frequently and consistently than any tech company. Reports also suggest that Apple’s device will cost $3,500— seven times the cost of the Quest 3, which will probably drive many households that want the Cupertino company’s headset to instead go with the one from Menlo Park. Amazon saw a similar benefit with its Fire Tablet, which launched a year after the iPad, but at 40% of price, whereas the Quest 3 is 85% less.

Over its first 12 or so months, the Quest 2 outsold the Quest 1 (May 2019) by a factor of 10, or 10MM to 1M. Such a steep change is unlikely for the Quest 3, but some multiple seems well within reach. Furthermore, these sales may sustain better than the Quest 2, which saw sales slow considerably in its second and now third years in market—during which Meta’s costs surged, leading to a doubling of annual net losses. Meta is also suggesting that the device will no longer be sold quite so far below cost (Meta likely lost about $150 per Quest 2, i.e. $1.5B for every 10MM units). This will harm sales but also reduce losses. With this in mind, it’s likely that Meta’s losses peak in 2023—perhaps to the tune of $16B or $17B—and then improve every year thereafter. Still, annual net profits seem far off. And if so, then Meta’s cumulative losses might cross $80B first.

These figures are stunning. They partly, though not exclusively reflect how brutally difficult XR devices have proven to be since Meta, Microsoft, Google, and others began investing in the form factor a decade and a half ago. At the time, many believed that there would be a few hundred million “wearable” supercomputers in use by 2023, if not more. But the number of technical challenges, as well as their difficulty, has gotten in the way of these sales, even as it amped up the investment required to get to a “minimum viable product” (I wrote about these challenges in detail here). To this end, Meta reports that 90% of its investments in the category are hardware-related innovations in optics, microLEDs, batteries, cameras, sensors, and the like.

Related Essay: Why VR/AR Gets Farther Away as It Comes Into Focus

The difficulty of producing an “MVP” XR headset has prompted most of Meta’s competitors, with the exception of Apple, to effectively abandon their XR ambitions—or at least to place them into hibernation pending new (and external) advances in the field. For Meta, these changes are both good and bad news. On the one hand, the competitive field has thinned. On the other hand, the company’s bet is increasingly contrarian, increasingly behind schedule, and substantially (for this very reason) more costly. For these investments to generate a positive return, they’ll need to generate at least $100B in cash flow—preferably in the next 15 years. Such a sum is theoretically achievable. In fact, the very product that Meta’s XR devices are designed to supplant—smartphones—have generated several times as much just in the past decade alone. But this is no ordinary watermark—after all, the iPhone is the most successful product in the history of capitalism.

"I think the world should be saying 'thank you Mark for advancing this technology.' I don't know that it's great for shareholders. That's debatable; he thinks that it is... [but] I wouldn't be against him... I think there's good odds for it, but whether it works out or not commercially, it's an incredible advance in technology... and they're really moving it ahead and it will really benefit all of us"

- Reed Hastings, Founder of Netflix and Former Facebook Board Member (2011-2019) in January 2023

Meta’s metaverse investments are high-profile due to the company’s name change, purported focus, and most importantly, decision to disclose these investments separately. But these investments are far from unique. In AR/VR, for example, Snap, which has a $15B market cap, has spent at least $1.5B acquiring AR startups in the last five years, plus billions more in R&D (20% of their 5,000+ employees focused on AR hardware in 2022) as well as its investments to publicly launch four Spectacles AR models. These proved unsustainable for Snap, which effectively shut down its efforts to build a device and laid off all dedicated employees in the back half of 2022 and early 2023. Yet AR/VR is not the only computing category that has seen such extraordinary investment with, thus far, limited financial return.

Beyond AR/VR

In his April 2015 letter to shareholders, Amazon founder/CEO Jeff Bezos listed the four requirements for a “dreamy business”: “Customers love it, it can grow to very large size, it has strong returns on capital, and it’s durable in time—with the potential to endure for decades.” Bezos added that Amazon (and thus its shareholders) had three such businesses—Marketplace, Prime, and Amazon Web Services—and that he hoped to build more.

Everyone wants a “dreamy business,” but part of what makes Amazon so unique is that the creation of new businesses is one of its core competencies, as Benedict Evans and Ben Thompson have varyingly described. Amazon has created or pioneered dozens of other businesses—often in areas where it had no prior experience, such as its dreamy cloud services, as well as the Kindle business, which is not dreamy but helped establish the ebook business and aided the company’s later investments in hardware. Creating new businesses is an extraordinary talent and arguably the most important a company can have over the long run.

But 2014, the year that Bezos’s letter addressed, saw the largest new business failure in Amazon’s 20-year history. In July, the company released its first (and only) smartphone, the Fire Phone. Unlike Amazon’s other hardware plays, it was fairly late to market. The Kindle was not the first e-reader, but it effectively pioneered the category. The Kindle Fire tablet debuted barely after the iPad. The Fire Phone, meanwhile, came seven years after the iPhone, six after Android, and at a comparable price. Amazon hoped to differentiate the Fire Phone through the integration of Amazon’s e-commerce platform as well as its use of advanced “3D cameras and sensors” that could scan and understand a user’s local environment (ideally to help the user purchase something that caught their eye). The device was an outright flop, terminated barely three months after its debut, with an Amazon-record $170MM writedown in the process (nearly half of which was for unsold inventory). A decade has passed since the Fire Phone, and it is still the company’s largest writedown and flop.

Normally, a dud like the Fire Phone would squash a company’s ambitions—at least when it came to building consumer computing devices. Making matters worse, the Kindle, while still a success, was in its third consecutive year of decline as tablets and smartphones robbed it of share and the annual updates to various Kindle models became more marginal, leading many current Kindle owners to replace their old devices only when they had broken. And while the Fire Tablet was still doing well, it was mostly a low-cost TV player, rather than the computing platform Amazon had originally envisioned. But the company was not deterred; dreamy businesses aren’t easy and they’re rarely cheap. AWS, after all, had cost tens of billions to get started.

In the years that followed, it was increasingly important to Bezos that shareholders understand the difficulty of big bets as well as their rationale. In 2016, he told The Washington Post’s Marty Baron, “If you think that’s a big failure, we’re working on much bigger failures right now—and I am not kidding,” he said. “Some of them are going to make the Fire Phone look like a tiny little blip.” In his note to shareholders the following year, he reiterated the point, writing, “As a company grows, everything needs to scale, including the size of your failed experiments. If the size of your failures isn’t growing, you’re not going to be inventing at a size that can actually move the needle.” Bezos also argued that the typical analogies for success actually limit the appetite for risk: “We all know that if you swing for the fences, you’re going to strike out a lot, but you’re also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs.”

By this time, we also knew which specific businesses Bezos thought might be the next home run. A few months earlier, he told Recode’s Walt Mossberg that Prime Video and Alexa were the top prospects for a “fourth pillar” at Amazon.

At the time, Prime Video was spending an estimated $3B on content annually, a figure that has since grown to nearly $7B. We don’t know the revenue, nor the broader cost basis, but cumulative content investments are probably about $35 billion. Even if Prime Video is, on a direct basis, unprofitable, the upside is obvious because the market already exists and the opportunities in digital delivery is clear. Video is the most valuable leisure category globally, generating more than $700B in revenue, but less than $150B is currently streamed. Among subscription video services, Prime Video is now the third-largest globally. It also helps Amazon participate in the rest of the digital video space, such as TVOD (where Amazon has a 40% share of a $20B+ market, collecting 15–30% gross margins), subscription reselling (25% share in a $25B market, collecting 15–30% gross margins), and connected TVs (40% share). Prime Video also provides Amazon’s enormous advertising business with more ad inventory and expands its ad product into premium video and, most importantly, live premium video.

Alexa was Amazon’s more speculative bet. Rather than disrupt a century-old market while it transitioned to a new medium, Alexa sought to pioneer a new market and medium altogether. Instead of trying to participate in a multi-player ecosystem, it wanted to serve as the foundation for one. Beyond building out a new business line for Amazon, Alexa would drive Amazon’s entire business—from e-commerce to AWS, Audible to Kindle. And while Prime Video, which launched in 2011, was launched out of Amazon’s five-year-old digital video store, Alexa was brand-new. What’s more, it debuted only four months after the Fire Phone was launched and one month after it was canned. Alexa was also slow to start, selling 2.8MM units over its first two calendar years. But sales took off in 2016, with 8.5MM units shipped, while 2017 saw sales grow more than 300% to 25MM. In 2021, over 65MM units were shipped.

Today, lifetime sales are estimated at more than 300MM. In addition, Alexa boasts more than two-thirds of the smart speaker market, having successfully fought off Google’s own smart speaker line as well as Apple’s HomePod, which was released in 2018 and then effectively discontinued for two and a half years. There are many measures of success, but ejecting Apple from a category is a pretty good one. Furthermore, the Alexa platform had been widely deployed into third-party vehicles, such as those of Ford and Toyota, as well as speaker systems, such as those of Sonos. Despite these topline achievements, the behind-the-scenes performance seems to have been more troubled.

Unlike Meta’s Reality Labs, we don’t know the P&L of Alexa. The New York Times reported that the division lost $5B in 2018. A basic modeling exercise using Alexa’s founding in 2012, reported sales figures, and the New York Times report would place cumulative losses for 2012 through 2017 around $11B. According to Business Insider, which claims to have seen internal documents, Amazon’s Devices and Services division lost $10B in 2022. We don’t know how much of this was had to do with Alexa/Echo, as the division also includes money-losing businesses such as Luna (Amazon’s cloud gaming platform) and profitable ones like the Kindle. As such, it’s possible Alexa lost more or less than $10B. But various Wall Street estimates place the figure around $8B (we know the division had at least 10,000 full-time employees in 2022, suggesting that the fully loaded cost of labor was already in the $4–6B range; a DoJ suit suggests that in 2019, there were at least 15,000 employees with access to Alexa recordings, suggesting total employees on the project was far higher).

A straight-line assumption from 2018 to 2022 would therefore mean that the interim years accumulated $18.5B in further losses. In total, this would mean $43B in losses for Alexa from 2012 through 2022.

I’m somewhat skeptical that Amazon could have lost that much money on Alexa. That said, the sum is identical to my Meta forecast over that same period and that sum was surprising, too, and had resulted in fewer than 30MM shipped units to Alexa’s 300MM. Amazon’s 2022 and 2023 rounds of layoffs are also understood to have hit the Alexa groups harder than any other group at Amazon. The Alexa division is also believed to included Amazon’s AR glasses R&D, which we know from Meta is quite costly. But even if actual losses are half of the above, or $20B, that’s still a remarkable sum.

Alexa’s core problem was usage. The most common requests of the Alexa platform were to play music, set a timer or reminder, and turn on the lights. These queries required very little “AI,” nor were they diverse enough to develop much of an ecosystem. In fact, Alexa doesn’t seem to have driven much commerce to Amazon, either. One 2022 report from Consumer Intelligence Research Partners suggested that only 25% of Alexa owners have ever used the device to make a purchase. Internal documents reviewed by The Information in 2018 showed that only 2% of users had made a purchase in the preceding 12 months, suggesting that even the disappointing 25% share was almost certainly inflated by one-time purchases (likely by new owners). Without even allocated revenues from Amazon, it looks like the Alexa P&L was mostly just R&D, marketing, and distribution costs, as the units themselves were typically sold at or below cost.

Data or Cost Centers

Another comparison comes from cloud infrastructure services, where Amazon’s AWS (launched in 2002) has approximately 37% of market share (excluding China). Azure, nominally founded in 2008, though built in part on Microsoft’s earlier exchange solutions, holds 22%. 2008 also saw Google launch Google Cloud, which the company viewed as both a strategic necessity and a lucrative commercial opportunity. Since then, net losses have hit nearly $35B. During this same time, AWS generated nearly three times as much in profit. In fact, 2022 was the first year Google Cloud’s topline exceeded AWS’s bottomline.

In contrast to Meta’s Reality Labs and Amazon’s Alexa investments, there is clear evidence of Google Cloud’s improving prospects. Annual losses have halved from their peak of $5.6B on $13B in revenue in 2020 (−43%) to $2.9B in 2022 (−11%), and in Q1 2023, the division booked its first profit, $191MM on 7.5B, or 2.6% margins. Most analysts expect the division to remain in the black going forward. Still, forecasts suggest Google Cloud won’t reach cumulative breakeven until the 2030s (it won’t be IRR positive until years later,). That’s a literal quarter century and not guaranteed, either.

Oh Platform Oh Platform

Though we typically think of a platform as being “digital,” there is no such requirement. A platform is any infrastructure or product that third parties can build upon. This includes iOS, Alexa, and AWS as well as the U.S. Interstate Highway System, Mattel’s Barbie, and Lego.

There are many ways to monetize a platform, few of which are mutually exclusive. For example, the owners can charge upfront fees to end users (e.g., buying Windows 98) or to third parties that want to sell their own products using that platform (Dell shipping a PC running Windows). A platform is also optimally positioned to offer adjacent services to its customers or users (such as ad products, productivity software, analytics). However, the most common form of platform monetization is the collection of “rents” from the third parties that build on top of it. This model also tends to be the best one, too, as it allows the platform to directly benefit from the value they create as well as leverage the investments of all its developer partners, thereby gaining access to their many total addressable markets, or TAMs.

The rent model is also why digital platforms are particularly valuable. Every person and company uses the Internet and computing devices (making it a far larger market than just a road system or toy), and there’s no constraint to how many customers can be served at once (Barbie doesn’t appeal to all toy buyers, nor can everyone use a highway at once without making the highway worse), while the marginal costs from incremental revenue are essentially zero (meaning every sale goes straight to the bottom line).

To this end, it’s notable that almost all of the most valuable companies in the world operate digital platforms that support billions of daily users and tens of billions of dollars in economic value daily. iOS is owned by the world’s most valuable company, Apple, while Android is owned by the number-three entrant, Google. Google also operates Google Search and Chrome, the top two platforms of the World Wide Web. The second-most-valuable company, Microsoft, owns Windows, the third-most-used operating system, as well as Azure, the second-most-used cloud infrastructure provider. The world’s fourth-largest company, Amazon, has a distant fourth-place OS, Fire, which runs on its tablets, TVs, and digital assistants (500MM+ total sold), but also the leading cloud service platform (AWS). Though not a strictly digital platform, it’s worth highlighting that three-quarters of Amazon’s e-commerce sales are through its third-party marketplace—an infrastructure platform where independent sellers/businesses sell through amazon and its fulfillment/payment service but set their own prices and hold their own inventory costs, rather than wholesale to Amazon. Facebook, the world’s ninth-largest company, operates the largest identity platform globally, with thousands of websites and applications using its “Log-in With Facebook” feature in lieu of, or alongside, their proprietary customer ID system.

Though a platform does not technically require developers or users to be a platform, this is a practical threshold. Epic Games founder/CEO Tim Sweeney has said that he “[adheres] to the 1990's definition that something is a platform when the majority of content people spend time with is created by others.” Bill Gates reportedly defines a platform as “when the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it”, while highlighting that Facebook would not meet this definition as barely any users or developers generated meaningful income from using it (Barbie would also fall short here). Horace Deidu uses the term “ecosystem” to differentiate between aspirant and actual platforms, saying that an ecosystem “implies the acceptance of a platform by a large base of developers.”

Regardless of the technical definition, it is the ecosystem that makes a platform so powerful. Not only does the ecosystem generate “rents” and provide extra value to users, it produces powerful barriers to market entry. In the early 2010s, Amazon and Microsoft both tried to launch smartphones to rival iOS or Android. But no matter their corporate investment, they could not alone build an ecosystem. And without the ecosystem, why would users adopt these platforms? And without users, why would developers make apps for them? After all, the Fire Phone was an Android fork, rather than a wholly unique operating system, thereby making it fairly easy for developers to port their app over. Few bothered anyway.

Over the past decade, the strength of the major mobile platforms has intensified as their ecosystems have grown in scale, complexity, and global importance. They have also explicitly strengthened their controls, too. This in turn makes these platforms more financially valuable and more difficult to replicate. Again, this is not unique to digital platforms, but it’s far more valuable given the flexibility of what can run on these platforms (versus, say, Barbie or a given toll road) and the low-or-even-zero marginal cost from operations. Here, Apple is a key case study.

For the company’s first few decades, Apple’s strength was typically attributed to the rich integration of hardware and operating system. In recent years, Apple’s tight integration has expanded into first-party software and services, the distribution of third-party software and services, digital and real-world payments, web browser engines, identity, messaging, and standards. This growing bundle doesn’t just give Apple more profit streams and make its ecosystem more attractive to users and developers alike; it also provides Apple with considerable hard, soft, and even accidental power.

For example, Apple essentially bans some business models from existing on mobile devices. Xbox, Nvidia, PlayStation, Google, and Facebook have all tried to build cloud gaming services on iOS, but such applications are effectively prohibited by Apple. As a result, these services are relegated to the browser, which makes Bluetooth/Wi-Fi controller connections flimsy and friction-filled, most forms of notification impossible (such as a friend sending you an invite to play), among other impediments (there’s a reason we watch Netflix in app versus in browser—and that’s just a video player!). In other cases, certain types of businesses are outright banned from having apps. One example is pornography. Three of the eleven most visited sites in the world (excluding China) are pornographic, yet none have an iPhone or iPad app—it’s not permitted.

iOS and to a lesser extent Android also dictate the economics of mobile software (e.g., 30% commissions) as well as specific prices, among other commercial terms. This in turn influences not just the margins of many business models in the modern era but also their priorities. The growing focus on ad revenues in video games and video streaming is partly a result of the fact that iOS and Android take no commission on such revenues. Many previously ad-focused businesses, such as Facebook, Snapchat, and Twitter, launched their paid subscription offerings following Apple’s IDFA/ATT changes (discussed below).

Through their devices, browsers, and stores, Apple and Android also have influence over the standards of the Internet—namely, which proposed standards can ever become real standards and when. Growth in browser-based games has been severely impeded by Apple’s slow and incomplete adoption of WebGL and OpenGL, which are needed to perform rich 2D/3D graphics without a native application. And in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Apple famously rejected Flash, the most popular web-based multimedia software platform, effectively sentencing it to death. In both cases, critics argued that Apple wanted to push developers and gamers away from the open web and towards its closed App Store, where Apple not only controlled what was released and how, but also took 30% of sales. Some have also suggested Apple’s rejection of cloud gaming services was similarly motivated. The rise of cloud-rendering threatened to diminish the importance of mobile hardware, the core of Apple’s business, while third-party game bundles would disintermediate Apple from both developers and users.

Then there’s offense. As we saw with Apple’s 2021 deprecation of identifiers for advertisers (IDFA) and implementation of app tracking transparency (ATT), a policy change by one of the major platforms can also instantly and deeply harm a competitor. In 2022, Meta estimated that IDFA/ATT cost it $10B in profits in that year alone. For similar reasons, dominant platform owners can use their influence to rapidly gain share in categories that they’ve ignored for years and that competitors have long since conquered. In 2021, Apple mandated that any application that supported third-party account systems (e.g., if you could log in to the New York Times appwith a Facebook account), the application would also need to support with a iCloud login. Of course, this effectively meant that the application had to support iCloud login everywhere else (e.g., Web, Roku devices, Androids) so that users could log in when not using their iOS device! As a result, Apple was able to rapidly become one of the largest identity providers on the Internet even though its solution came to market decades after the market leaders and offered limited experiential differentiation. And by providing this service, Apple is able to track and understand the behaviors of iOS users across the devices of its competitors.

In 2014, Apple launched Apple Pay, enabling iOS users to make mobile payments simply by touching their device to a payment terminal. Other payment mobile payment networks, such as Square, as well as banks and credit card companies, such as Chase and Visa, are allowed to have iOS apps, but they cannot use the NFC chip that enables tap-and-go payments. Accordingly, these other apps can only do barcode or QR code–based payments, which are slower and more clumsy to use. Apple claims its NFC payment restrictions are security-related, yet Apple it does allow developers to access the NFC chip in order to unlock car, hotel, or home doors - categories in which Apple does not compete. And if Apple chose to, it could limit who can use the NFC chip for payments (e.g. Visa, Chase) and the size of the transaction (e.g. $50 or less). No surprise, Apple Pay has an estimated 90% share of mobile payments on iOS devices and 7% of all online payments as a result. And crucially, each transaction nets Apple 0.15% of the transaction — even if Apple Pay processes it using the customer’s underlying Visa or Mastercard!

Apple has a similar approach to its new government identity verification program. In several states, iOS users can now upload their state ID or driver’s license to Apple Wallet and then use their purely digital reproduction to board a plane or sign a deed, with Apple authenticating the user via FaceID. But while third party apps, such as Chase and Visa, are allowed to use Apple’s FaceID for the purpose of log-in authentication, they cannot use an iOS device’s IR scanner to build and operate their own facial recognition database and system. As such, no other app or service, whether it’s Equifax or even a state DMV, can authenticate a user using their face - just display a photo of the supposed user.

Examples such as Apple Pay, iCloud ID, and FaceID are many. For the iPhone’s first five years, it came preloaded with Google Maps. But in 2012, Apple launched its own map application, which then came preloaded instead of Google’s. Although most consumers and experts considered Apple’s app far inferior (at the time, Google had 8,000 employees working on its mapping products, while Apple had 14,000 non-retail employees in total), by 2015 it had nearly 80% usage share on iOS devices. While Apple has allowed third-party browsers on iOS devices since 2012, this is only nominally true. Competitors are not allowed to use their own engines but must instead wrap a skin on Apple’s own browser engine (Safari WebKit)—and they can typically only use an outdated (i.e. inferior) version of this engine compared to Apple’s own iOS Safari browser. Given that Safari is pre-installed, natively integrated, and often more performant, it’s no surprise that it holds 90% share of iOS devices. Although Apple Music debuted four years after Spotify in the United States, it passed the first-movers within three years of launch. Adoption here was aided not just by native integration into iOS devices but by also targeted promotions not available to anyone but Apple (e.g., free trials advertised in iOS’ settings menu).

Just as Apple’s ecosystem has strengthened over time, so too has its penetration and profits. iOS now holds nearly 60% market share in the United States, an estimated 75% of new smartphone sales, and more than 90% share among teens. Globally, Apple holds less than a quarter of total market share—but it receives more than two-thirds of mobile software revenues due to its ability to attract the most valuable users and out-monetize them, too. In total, Apple manages (i.e., bills for) nearly 1B monthly subscriptions operated by third-party developers. Based on Apple’s 2020 figures and methodology, it looks like roughly $700–800B was spent via iOS apps in 2022 (including in-app purchases for physical goods and services), equivalent to 0.75% of world GDP. The results for Apple have been extraordinary and durable. From the debut of the iPhone in 2007 through Q4 2022, Apple generated nearly $915B in operating cash flow.

Apple is the best example of the ecosystem effect because its platform is both closed and tightly managed, and the company books 40%+ margins on its hardware as well as 90%+ margins on all eligible transactions that happen on its device. But while Google has a very different model – the Android OS is open-source, Google makes almost none of the devices which run its OS, and it shares its store revenues with device-makers and wireless carriers – the company has built in similar controls.

Though widely considered to be Google’s mobile operating system, the Android operating system is technically open-source and is managed by the nonprofit Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of nearly 100 device makers, network operators, and chips companies. Any smartphone manufacturer, whether members of OHA or not, is free to use Android as they like. For example, an OEM could fork Android to make it their own and prevent others from using their variant. Or they could choose to use Android, but take none of Google’s apps or services and instead exclusively integrate their own competing software suite. However, nearly ever Android OEM outside of China, with the exception of Amazon (which forked Android to create its Fire OS), uses Google’s end-to-end version of Android. This means that Google Search is the default search engine; the user’s core smartphone account must be a Gmail account; Google’s suite of apps must be preinstalled and natively integrated; and the device must observe Google’s policies on data and security as well as the company’s various UI/X specifications.

Android OEMs support Google’s version of Android on an end-to-end rather than piecemeal basis, because they can’t do so on a piecemeal basis. If an OEM wants their device to include the Google Play app store or support Google Maps or Google’s YouTube app, they must first support Google Play Services. To receive Google Play Services, the OEM must make Google Search the default search engine and preinstall a laundry list of Google apps and services (which the user is naturally blocked from deleting) and conform to a variety of policies from aesthetics to data management and tracking. OEMs also must also sign agreements not to fork Android or sell devices with a forked version of Android. In exchange for the above, Google also shares some of its Android revenue with OEMs—they receive a portion of search-related revenues from their respective devices as well as a cut of app store profits.

Over time, Google has moved many of Android’s core functions (e.g., background services, libraries) into Google Play Services and also expanded Google Play Services to include health and fitness, payment processing, native advertising, and the like. Many analysts considered Google’s de facto and creeping closure of Android to be a response to Samsung’s growing success with the operating system. In 2012, the South Korean giant sold nearly 40% of Android-powered smartphones (and the majority of high-end ones)—more than seven times as many as the second-largest manufacturer, Huawei. In addition, Samsung had become increasingly aggressive with its alterations to the “stock” version of Android, producing and marketing its own interface (TouchWiz), while also preloading its devices with its own suite of apps, many of which competed with those offered by Google. Samsung even added its own mobile app store. Samsung’s success as an Android manufacturer is inarguably connected to these investments, but their approach is not dissimilar from forking. Regardless, Samsung’s upstart TouchWiz “OS” threatened to disintermediate Google from its developers and users.

As Android approaches its fifteenth anniversary since release, it’s clear that it serves a different role than pitched in 2008. At the time, Google positioned the “open source OS” as a collective effort to build a shared ecosystem. To OEMs, Android was not just a free alternative to licensing Windows Mobile but an opportunity to participate in mobile app revenues, steward the platform’s overall development, and develop OS-level services without needing to develop and manage the underlying OS itself. For wireless operators, it was an opportunity to benefit from application-layer profits and diversify from Apple. Now Google is effectively paying its partners to deploy all of its services, not just Android, while also blocking them from touting competing services or deploying their own. And if they choose to support a rival, substitute in their own services, or otherwise become noncompliant, then the OEM’s users—having already bought OEM’s device—will lose access to all of Google’s apps and service-level integrations such as cloud backup and will need to reinstall all third-party apps from an app store they’ve never used before and which might lack some of their apps, too.

Google boasts that it has six products with 2B users and a dozen with 500MM, but the popularity of these products flows naturally from Android’s 2.5B+ users (third icon above). If you use Android, your native search engine is Google Search, email client Gmail, browser Chrome, map is Google Maps, photo app is Google Photo, SMS client is Google Messages, camera app is Google’s Camera app, etc. Most of Google’s apps cannot be deleted by the user, either. It’s a touch odd that these are positioned as different products to investors, but for Android OEMs, they are a mandatory part of “Android”.

The challenges of breaking away from Android in 2023 are the same as building any new smartphone platform in 2023. A challenger needs to produce a device so great that users will not just prefer it to the market leaders but be willing to adopt it while its ecosystem is smaller and/or abandon the ecosystem in which they’ve already invested. This is a high bar, and it gets higher every year. Microsoft Windows Phone (2010) and Amazon’s Fire Phone (2014) launched at a time when most people had yet to adopt a smartphone (half of Americans didn’t have a smartphone until 2014, while half the world didn’t until 2020). Today, nearly everyone has a smartphone. As such, building a user base taking share from competitors whose customers and developers have invested as much as fifteen years into the platform. Furthermore, smartphone replacement cycles have elongated from barely 24 months to more than 36 months globally, meaning it takes 50% longer to take share. The ease and pace of adoption matters because any differentiation offered by an insurgent must endure long enough for the insurgent to build a sizable ecosystem. If Amazon’s multi-sensor functionality proved popular, it likely would have appeared in the iPhone within two or three updates, and probably with better performance. Android was first to multitasking, large screen sizes, widgets, and high-quality cameras, but these features converted almost no iOS users and were ultimately embraced by Apple anyway. It’s telling that Samsung, which boasts over a billion Android users, is unwilling to break from Google’s Android users in order to grow its profits or controls. Although Samsung has its own app store and services, and a forked version of Android would run nearly all Android apps, the company cannot plausibly substitute for all of Google’s products, from Google Maps to Gmail and YouTube.

In many ways, the cloud market is more permissive than smartphone operating systems. Many companies are multi-cloud, using a pair or more bedrock-level providers (e.g., Azure and AWS) as well as a series of specialty providers (Snowflake, Equinix, etc.). Few people use multiple mobile operating systems. And while most consumers now have smartphones, many businesses have yet to migrate off-premise or have some operations yet to move off-premise. However, the ties to existing ecosystems are even deeper and often slower-moving. Cloud customers build their systems using various APIs, systems, and conventions unique to their cloud provider and often benefit from multi-product bundles that make it financially impractical to move parts of their business or processes to a new cloud provider. Changing providers also means extensive, costly, and risk-filled “process transformation” and employee retraining. As such, competitors need to offer more than marginally better prices, customer service, or products—as Google Cloud has learned.

The Attack

In the last section, I discussed how dominant ecosystems can take value from or outright invade the various applications that run on their system as well as the difficulty and cost of building a rival ecosystem. Another way to understand this power dynamic is to look at it in reverse—to investigate what it would take to attack a single existing application or service protected by a dominant ecosystem.

One such indicator is Google’s 15+ years of paying Apple to be the default search engine on iOS and Mac. According to estimates from Goldman Sachs, these payments have exceeded $120B, with nearly $20B expected this year. Google’s 2022 payment was equivalent to a third of Google’s entire net income and increased Apple’s by a full 25%. Moreover, Google’s payments to Apple fund more than three quarter’s of the later company’s R&D expense.

This may seem like an unfair analogy. Google is paying for profitable distribution into a third-party platform, not investing to build a platform. But there are other possible characterizations. For example, one could argue that Apple, not Google, has the most profitable search engine in the world via its iPhone and iPad. However, it monetizes this search engine (or rather, search bar) by being paid by another party for the right to answer an Apple user’s query. Supporting this hypothesis is the well-known fact that Apple hates when third parties collect the data of Apple’s users – and especially hates when this data is then used to target them. Despite this, the tech giant nevertheless opts to take Google’s cheque instead of offering its own service. And of course, Apple could generate billions from its own search engine. As such, Google’s iOS strategy requires the company to give Apple more money than Apple would be able to make directly. The largesse of Google’s payments also makes it difficult for another search engine to displace the company on iOS.

Another point of evidence comes via Google’s own smartphone platform, Android. Google’s payments to Apple are estimated to be equivalent to (or rather, paid as) 25% of the revenue Google generates from iOS-based queries. In contrast, Google pays only 11% of revenue to Android partners. To this end, some have argued that the primary business model for (or at least profit driver from) Android isn’t even the platform itself, it’s saving money on the billions of queries Google would otherwise have to buy from Apple. And if Google is spending $20B a year to Apple and $5–7B more to Androids partners just to maintain its 93% share of search and prevent competition, what would it cost to build one? We may soon find out.

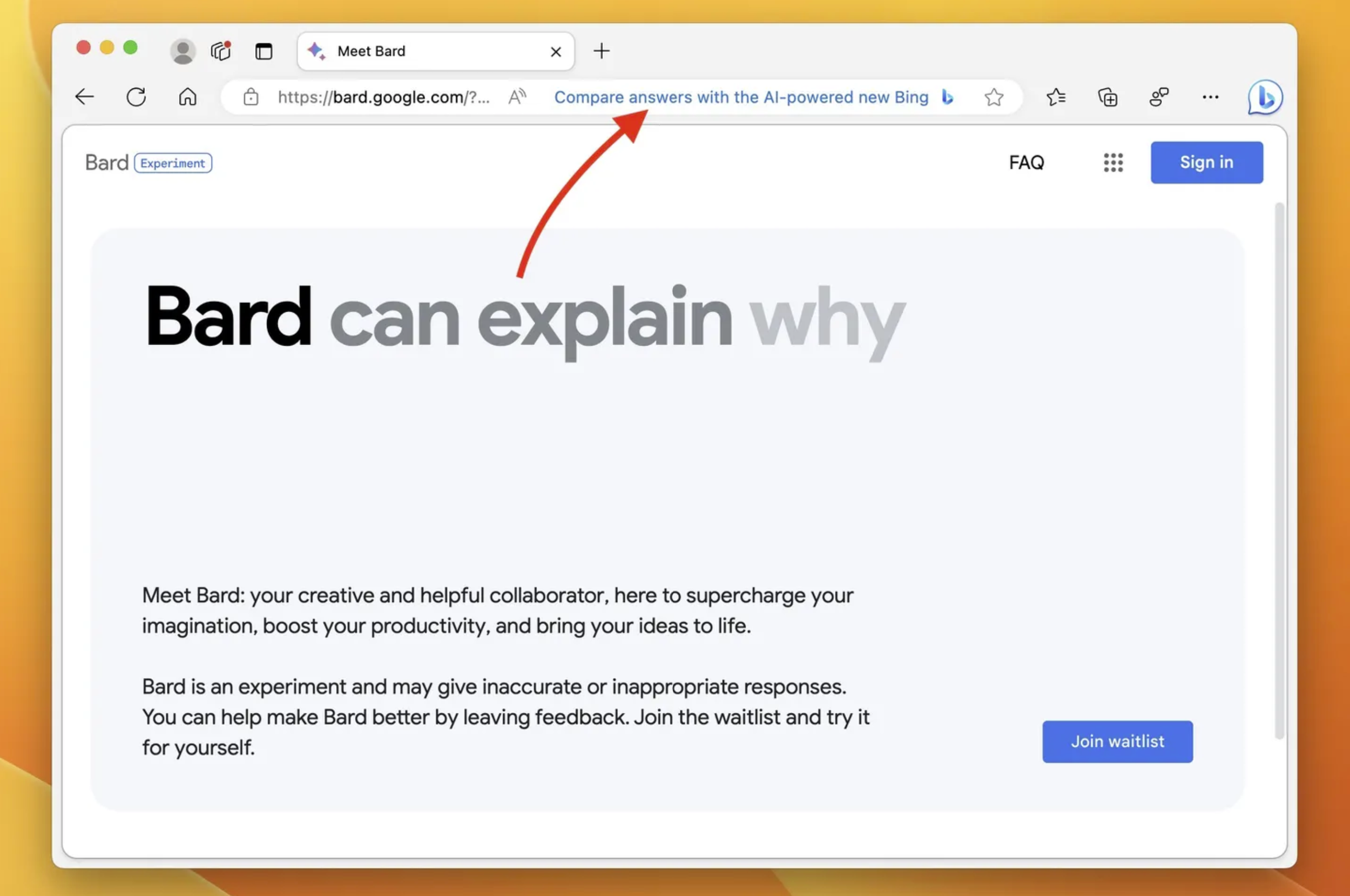

Through AI, Microsoft hopes that Bing can grow its 3% of the global search market. Yet even the company’s preparatory maneuvers have been expensive. Since 2019, Microsoft has invested $13B in OpenAI and spent $1–2 billion building dedicated servers to operate the products. The company has also provided the startup with free access to its presumably valuable training data. True, there are some caveats to the investment figures. Microsoft now owns 49% of OpenAI and will receive 75% of OpenAI’s profits until its investments are paid back. As such, Microsoft’s $13B are not exactly outlays. OpenAI also supports far more than just Bing. However, OpenAI is also directly competing with Microsoft in many product categories, including search (OpenAI just launched its own search-focused iOS app) and can make its technologies available to Microsoft’s competitors too (DuckDuckGo now uses ChatGPT to power its DuckAssist service, while Microsoft’s CRM rival Salesforce has used ChatGPT to build its EinsteinGPT, which competes with many of Microsoft Office’s ChatGPT-based features). These offerings and deals weaken the differentiation of Microsoft’s AI-based offerings and their margins, too. Microsoft could always try to buy OpenAI outright, but that would add tens of billions more to its already-expensive foray.

Despite these large upfront costs and limitations, Microsoft still has a tough and expensive path to gaining further share—even if New Bing deserves it, just as the original Google Search deserved to beat AltaVista, WebCrawler, and Yahoo! This is because Google beat the incumbents on open platforms (i.e., PC and Mac), and it did so at a time when governments were unbundling Microsoft’s Windows from its Internet Explorer. Furthermore, Google’s growth in search was bolstered by and is now protected by the concurrent adoption of Gmail and Chrome, two products that handily beat market leaders AOL/Hotmail and Internet Explorer/Netscape, respectively. The path for Microsoft is far more difficult.

There are 2.5B Google Android users, with each device defaulted to Google Search and Google Chrome, which itself also defaults to Google Search. In April, reports emerged that Microsoft had approached Samsung about paying the OEM to replace Google with the new OpenAI-powered Bing Search Engine. Samsung eventually considered the move impossible for the aforementioned reasons. On PC/Mac, Microsoft has some advantages through its ownership of Windows, but it must nevertheless contend with Google Chrome’s 66% share across both desktop/laptop OSs, the 12% held by Safari (where Google also pays for Search Default), 6% by Firefox (same), 3% by Opera (same). Microsoft’s Edge holds 11% share and thus includes Bing.

The remaining 1.3B iOS users (and 1.8B iOS devices)… that would require Microsoft to win a bidding war with Google that starts at $25B annually. As Google pays Apple 25% of iOS-based search revenue, Bing could offer higher rates and a larger minimum guarantee. But $25B is more than twice Microsoft’s total ad revenue in 2022, while being barely 10% of Google’s. As such, Google can afford to profitably hike its payments far beyond Microsoft’s reasonable ability to pay them. Put another way, New Bing is fighting for market share in a world where 60% of queries are delivered by its biggest competitor’s platform (Android), and another 30% would probably cost $30–40B per year, all paid to one of its biggest competitors. Of course, it’s a bit exaggerated to say a search engine needs to be a platform’s default search engine to gain share of that platform’s users. But in practice, this is mostly true – even if a non-native app, product or service is far superior product. Recall Apple Map’s 4:1 share versus Google Maps on iOS, Safari’s 9:1 share versus Chrome, Apple Music taking 8:1 share of new subscriptions in the first 18 months after it was released in the US (which was four years after Spotify!). Most consider OpenAI to be better than Google’s Bard today, but that may not last and even if it does, it needs to be much better and perceptibly so.

In June 2023, Bing replaced the entire first fold of results from searching “Chrome” to general ad copy advertising the use of Bing and its benefits over Google Search and Bard. Less than 30 minutes after The Verge reported on the move, Microsoft turned it off.

Just as Microsoft has its eye on search, the company has said it plans to launch its own mobile gaming app store on EU-based iOS and Android devices next year, following the implementation of the EU’s Digital Markets act.

Powering this move is more than Microsoft’s present-day scale in gaming: 60MM+ Xbox owners, 100MM+ monthly Xbox Live users (which includes PC-based gamers), 150MM monthly Minecraft players, 25MM subscribers to Game Pass, and a rich library including Halo, Gears of War, and Elder Scrolls. In 2022, Microsoft announced that it was buying Activision Blizzard King, the largest independent gaming publisher outside of China, which counts hundreds of millions of monthly active users across franchises such as Call of Duty and Candy Crush, the majority of which are mobile users. The price tag? $75B including debt—the most expensive Big Tech acquisition in history. Still, precedent suggests far more will be needed.

When Epic launched its PC-only Epic Games Store in 2018, the company believed it had a solution to the “cold start” problem as well as several differentiators for players and publishers. To seed the platform, Epic transformed its Fortnite game launcher into its game store, thereby ensuring a Day One install base in the tens of millions and a daily active user base over ten million (which it correctly assumed would sustain for years). To appeal to developers, Epic offered 12% commissions on sales versus market leader Steam’s 30% in addition to greater ownership over a user’s game-related data. And if developers also used Epic’s Unreal Engine, which took a 5% royalty on revenue, Epic would count this 5% against Epic Games Store’s 12% commission, for a 7% net store fee. What’s more, publishers were not obligated to use EGS’s payment solutions (thereby enabling them to reduce commissions down to the 3–4% charged by payment processors) and could even distribute their own launchers/stores if they chose.

Users, meanwhile, would be able to keep and use any games they bought on Epic Games Store, even if they stopped using EGS to launch the title (unlike Steam). They would also have greater ownership over the awards and achievements they earn through EGS, too. And to attract new gamers and retain old ones, Epic also announced an ambitious “free games” program where 1–2 games, each of which with an average retail price of $22.50, would be available to download each week at no cost. In 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, a total of 364 games were made free, with a combined notional value of $8,222. During this time, gamers redeemed 2.4B copies (603MM per year), representing a notional value of $55.6B ($14B per year).

To be sure, Epic’s cost for these game giveaways would have been a fraction of the ostensible retail value that players redeemed. Nevertheless, the immense value given to users has done relatively little to generate revenue, let alone secure share.

In 2022, user spending on games other than those produced by Epic (e.g., Fortnite, Rocket League) was $355MM, up barely $100MM annually since its launch four years earlier. Given EGS’s 10% commission, these sums mean the platform’s net revenue from third-party titles was likely less than $40MM annually, with less than $125MM generated since 2019. On a percentage of revenue basis, EGS remains a 1P launcher (57%) rather than a 3P platform, as had been intended. Epic doesn’t report the breakdown of active users (peak DAU have grown from 11MM in 2019 to 34MM in 2022, with year-end MAU doubling to 64MM). But it seems likely that the majority of these users are just playing Fortnite and Rocket League (Epic reports these are two of EGS’s five most-played titles) or logging on to claim free games.

As Epic Games Store approaches its fifth anniversary, the path to profitability is hard to see. The company’s August 2020 P&L leaked as part of its trial against Apple, revealing that Epic did not expect EGS to breakeven until 2027 at the earliest. What’s more, EGS’s publicly reported revenues for 2020, 2021, and 2022 have subsequently fallen short of August 2020 forecasts. In addition, many top game publishers only selectively support the support the store (Take-Two’s catalogue titles Bioshock and GTA are available, but not the annually-updated NBA 2K series), while others skip it altogether (Activision Blizzard won’t even distribute its own store launcher through EGS). Without access to many of the most revenue generative titles in gaming, revenues will be even harder to come by.

EGS’ core challenge is that video game stores are ecosystems, not content stores in the way we think of Prime Video, or iTunes or Audible. These latter examples have their own form of lock-in, to be sure. If a household has spent hundreds of dollars on movies or TV series on iTunes, these “entitlements” are an impediment to leaving iTunes. However, these entitlements are not a large impediment to using Amazon’s Prime Video store from time-to-time – especially if Amazon offers a desired title at a lower fee. It’s also likely that these households are not frequently rewatching these old TV shows and films. What’s more, this household probably has anytime access to these titles at no additional fee via an SVOD subscription they already have – or could have for $5-15 per month (a modest fee that also includes thousands of hours of other content, too). For example, a family that has bought many Disney films on Prime Video is tied to Prime Video… until they get Disney+. Music is even easier. Whether you’re on Spotify or Apple Music, you’ve access to the exact same catalogue and at the exact same monthly fee. You can even import your playlists from one service to another, too. And as most media stores are not social experiences, most users don’t care whether their friends use one service or another; it has no bearing on their own experience.

But video game stores are more complicated than video, music, or audiobook stores. They manage not just purchase entitlements, but also the player’s achievements, trophies, and rewards from playing a game. This can be everything from whether they completed a game, whether they were in the first thousand players to complete the game, completed it without taking damage, completed it on extra hard mode, etc. These stores also manage a player’s social graph and player network – their ability to play with friends, be invited to play with friends, show off their trophies, etc. – as well as a network of game “mods” (UGC plug-ins of sorts).

In other cases, a store operates a game’s entire multiplayer/online stack, meaning that the very operation of the title is inseparable from the store (video, music, ebooks, audiobooks have no such comp). It’s also exceedingly common for players to play old games, even those more than a decade or two old. And almost none of these titles are available via all-you-can-eat subscription. Lastly, there’s a large gap between the size of the largest video games stores and smaller ones. As the most popular games are typically based on multiplayer experiences, as is the case with Call of Duty, Fortnite and Roblox, this means that a gamer’s choice of store is largely affected by which stores their friends use.

The complexity of a video game store ecosystem has made the PC store leader, Steam, unassailable and ever strengthening. After two decades in operation, there are tens of billions in game purchases locked to the Steam store across hundreds of millions of users, not to mention the billions of trophies and billions of user connections.

If a Steam user wants to leave Steam for EGS or any other store, then that player will need to give up the player networks, achievements, and entitlements they’ve established on Steam. This means embracing a smaller player base, manually rebuilding their player network, repurchasing games, and so on. If this user wants to use multiple stores, they must continue fragmenting their player networks and achievement (which are a form of social signaling for their player network). A similar version of this problem exists for developers. If the developer wants to stop supporting Steam, they face not just revenue challenges, as Steam has 70%+ market share on PC, but a complex and unfriendly distribution strategy. For example, their most loyal players will be forced to deprecate their historical achievements – a player’s first 12 years of Call of Duty awards might be on Steam, while new awards only on platform. The publisher will also be pushing its users to a platform that fewer of their friends use, too. And unless the publisher wants to shut down the titles currently available on Steam – which may be generating ongoing revenue and some players have already bought – then Steam will continue to sell and/or operate parts of the publisher’s catalogue, even as the publisher tries to market a Stream competitor. Lastly, Steam often obligates developers to MFN agreements that prevent rival stores from offering lower prices to consumers, or lower commissions to developers, thereby making it difficult for a rival to attract either group (hence Epic spending billions in game giveaways).

Evidence of Steam’s lock-in is clear beyond the struggles of EGS. In 2011, gaming giant Electronics Arts launched its own store, EA Origin, which would exclusively sell PC versions of its titles. The advantages of such a move were many: cutting distribution fees from 30% to 3% or less; avoiding disintermediation; fully controlling live services (e.g. multiplayer audio chat, updates, player reporting); increasing its ability to promote its own titles, etc. Eight years later, EA announced it would return to Steam. Activision Blizzard has spent 20 years trying to leave Steam, but except for free-to-play titles such as Call of Duty: Warzone, most of its titles continue to sell through the platform. Ubiquitous distribution aids both EA and Activision Blizzard’s portfolios, but their platform’s grow without exclusivity and prices advantages. Just imagine if Disney launched Disney+ at the same price as Netflix (versus 50% less), while continuing to release its library and originals on Netflix, and offering just a few unique account-level benefits in exchange (e.g. a Disney log-in and account image).

True, publisher-based stores are inherently less compelling than stores that sell the entire market. But to this end, we can note that Microsoft, too, has been unable to beat Steam, despite its ownership of Windows, the native integration of the Window’s Store and its Game Pass subscription into Windows, and the Xbox console ecosystem, which boasts tens of millions of users, billions of game entitlements, and billions in achievements/awards. And Amazon, the largest e-commerce platform in the world and owner of Twitch, the largest video game livestreaming service outside China, has also failed to gain any meaningful share of PC gaming—even after it began adding free games and in-game items to its popular Prime subscription.

The battles against Steam show how hard it is to build a gaming marketplace on third-party platforms. Even though it launched with a large Day One user base and ecosystem as well as one of the world’s most successful games and a strong two-sided value proposition that offered consumers and developers an alternative to Steam’s entitlement lock-ins, nearly all gamers and game gamers remain tied to Steam - which is estimated to generate $8B in revenue per year and several billion in profits.

WebPlease

A final area we can consider is crypto. While there is no single corporate investor here and instead hundreds of venture capital and private equity firms, the goal of these investments is effectively to construct a new decentralized internet—and with it, new applications, services, and systems that will displace today’s multi-trillion-dollar platform giants. Since 2012, roughly $87B has been invested into crypto/blockchain startups—a sum that excludes the tens of billions invested by institutions and retail investors directly into Layer 1s such as Ethereum and Layer 2s such as Polygon, as well as application-specific entities such as Render.

Crypto has yet to demonstrate utility or adoption commensurate with the capital invested or its market capitalization ($1.1T overall, or more appropriately, $600B, excluding Bitcoin, which is mostly just a cryptocurrency today). Furthermore, one of the key advantages of the crypto ecosystem is supposed to be its ability to jump-start the “cold start” problem. But there are important caveats.

Nearly 70% of total investment in crypto has occurred over the last 24 months, with the median dollar invested in September 2021. This is not a lot of time to produce hegemonic disruption. But during this time, the hegemons have done an effective job of stifling the adoption of crypto apps and services.

Today, neither Apple nor Xbox permits crypto applications. As such, any software/games/services that use NFTs or cryptocurrencies can only run on a web browser, which are largely incapable of rich 3D graphics, among other constraints. PlayStation doesn’t support crypto at all, browser or not.

Non-gaming applications are permitted on iOS, but their functionality is crippled. OpenSea’s NFT app can display NFTs – but you can’t buy or trade them unless Apple is given 30% of the transaction, an obvious deal-breaker given NFTs can run into the tens of millions of dollars. Were Apple to take 30% of every trade, the value of the NFT would have to grow by 43% in between each transaction for anyone other than Apple to be profiting from the NFT’s price appreciation. Which apps can even use crypto logins, services, or technologies remains purely under the discretion of these platforms, too. And when these are permitted, the underlying OS can still cram their products in. It’s hard to have a decentralized app when its distribution is managed by a centralized software store using a centralized ID (iCloud) owned by the wealthiest company in history.

None of this to say crypto is a good idea or that blockchains are a good system. But we can’t underestimate the significance of these impediments. Last year, many headlines touted that “gamers beat NFTs,” but the truth is, gamers never really got a chance to do so. Call of Duty couldn’t have crypto, for example, and the Minecraft mods that use NFTs were banned. The president and COO of Activision Blizzard left the company in December 2022 to become CEO of Yuga Labs (Bored Apes) and presumably would have liked to give the technology a test run if not more. In April 2023, Epic Games’ EVP of Development also joined Yuga Labs as CTO. If games, among other applications, cannot test blockchain integrations unless they give up most of their audience and some of their technical stacks, then audiences cannot reject them and developers can’t figure out how to improve them.

Dreaming of a Dreamy Business

The financial, offensive, and defensive power of the platform explains why Zuckerberg is pushing the limits of Meta’s balance sheet, Alexa so clearly fits Bezos’s home run theory, Google will spend a quarter century and tens of billions to build a business to the point of breakeven, and investors will plow tens of billions into crypto for a future they hope will be less profitable than the past. Though the accumulated losses are terrifying, they’re nevertheless dwarfed by the potential profits, as well as the security that comes from owning your own end-to-end platform versus relying on another.

In fact, it’s easy to overlook how the everyday operations of these companies, most obviously Meta and Amazon, are already affected by their intermediation by rival platforms. Meta, for example, is widely criticized for its reliance on ad revenues. However, the subscription-based products it wants to offer are sometimes prohibited by iOS and Android, and where they are permitted, Meta sends 30% of its revenues to its Big Tech competitors, even though those competitors invested not a dollar to build that revenue stream (and they incur no marginal costs, too). This is particularly problematic with creator economy products—if Apple or Google takes 30% and then Meta takes a cut, barely anything is left over for the creators. This flywheel doesn’t fly.

Amazon, meanwhile, no longer sends its customers item-by-item invoices and delivery updates via email because doing so would allow entities like Google (which owns Gmail), among others, to know what the user purchased and at what price. This is an obvious threat to Amazon’s business—one so great it doesn’t even give its customers the option to receive the information via email.

These issues are not going away. The digital economy continues to grow in size, diversity, complexity, importance, and connected devices. The result is that the leading platforms get stronger and more profitable. Last decade, Apple generated $600B in operating profits; this decade, it will reach that point by 2025. Fully 25% of the profits generated by AWS over the past 20 years occurred in the last 12 months.

It’s remarkable to consider that if Microsoft—the world’s second-most-valuable company—wants to grow its paltry 3% share of search, 60% of the market isn’t on the table due to Google’s control over Android and most of the remainder requires tens of billions of placement fees per year. To have a plausible share of mobile gaming app stores, Microsoft must spend tens of billions more on top of the tens of billions spent on its Xbox platform life-to-date, and record-breaking Activision Blizzard King acquisition of 2022. And launching a mobile gaming app store on iOS is only possible because the EU has forced Apple to allow competitors to its vertically integrated App Store (crucially, this means a store is only possible in the EU, at least for now). Indeed, one could argue that if Microsoft wants a large share in search and gaming and faces hundreds of billions in expenditures this decade to do so, it would be more cost-effective to build a new smartphone platform—or at least an Android fork. Imagine if Microsoft went to Samsung and other top Android OEMs, offering both greater revenue share than Google does with Search, as well as its suite of applications (e.g., Maps, Windows Store, Outlook IDs), for example? The required war chest would be enormous—but so too is spending $30–40B a year for 30% share of iOS search, and the upside from smartphone displacement is far larger.

Billfolds

More than ever, our economy runs on ecosystems. Not just broad partnerships, large commercial deals, or expansive networks, but ecosystems. It’s to our collective interest that there’s maximum competition at the foundational platform layer and every application and service layer, too. But the cost of competition is now in the tens of billions, if not more. In a weird way, Google Cloud is cheap at $35B, but most can’t spend that much, let alone wait fifteen years for losses to end and another decade or more to generate a net return. In fact, it’s likely Google couldn’t have invested as heavily were it not for near-zero interest rates over the past decade. And that the investment wouldn’t have worked at all were it not for Google’s own ecosystem, including the consumer-facing (and Android-integrated) Google Photos, Gmail, and Drive, as well as its enterprise offerings such as Workspace. The prohibitive cost of entry has led to phenomenal profits. Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon are now 21% of the S&P (Apple and Microsoft are so large that alone, they would be the second largest sector of the S&P, behind the rest of big tech, and ahead of energy and healthcare).

In many ways, OpenAI seems to refute the narrative outlined throughout this essay. According to The Information, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella asked his research chief last year, “Why do we have Microsoft Research at all?” given that in seven years and with only 250 employees, OpenAI had managed to outperform the AI systems produced by Microsoft’s decades-old and 1,500+ staffed research team. Yet OpenAI’s quest for dominance and scale is just getting started. As stated earlier, the company has already raised more than $11.3B, with Microsoft also investing billions more in computing infrastructure to support OpenAI’s training models. Furthermore, co-founder and CEO Sam Altman sold 49% of the company to Microsoft, which will also receive 75% of profits until that investment is paid back (Microsoft will retain its stake). That’s a hefty bill for OpenAI’s shareholders. What’s more, Microsoft is repackaging OpenAI to compete directly with it—going so far as to preemptively tell customers not to use OpenAI’s products but rather Bing’s version of them (customers are not told it’s using OpenAI). And of course, Apple takes 30% of all OpenAI subscriptions bought through iOS.

Moreover, Altman has reportedly told a panel of investors that OpenAI is “going to be the most capital-intensive startup in Silicon Valley history,” potentially needing as much as $100B. A hundred billion dollars! That fundraising alone would make it one of the 125 most valuable companies in the world.

Other platforms reiterate this. Elon Musk has estimated that Starlink will need at least $30B in investment to turn a profit—and its costs are subsidized by the success and scale of parent company SpaceX, the second-most-valuable startup in the world. An independent Starlink would be orders of magnitude more expensive. Amazon’s competitor, Project Kuiper, has an initial investment of $10B and is partnered with Blue Origin, an independent aerospace company that happens to owned by Jeff Bezos.

Of course, the upside from a successful platform and the probability it needs untold sums of money is not sufficient to justify endless investment. When a would-be platform fails, it’s rarely because of a lack of investment. Microsoft’s Windows Mobile, as well as Research in Motion’s BlackBerry, failed because they were just wrong. These platforms bet that the winning smartphone must have a battery that lasted for days, rather than one that supported only a few hours of use; that wireless data usage should be minimal, not used in abundance; that a smartphone would be the average person’s secondary computer, not the primary computer; that the market would be led by business customers, not ordinary consumers; that a physical keyboard was essential and a touchscreen optional at best; that the price had to be $200 or less, not $500 or more; that the device needed to survive being dropped and crushed and could not be fragile; and so on. Another issue is time. The right idea at the wrong time is still wrong—and sometimes because it's too early to build or integrate into an ecosystem. Even if you brought an iPhone to market back to 1995, you’d find that 3G had yet to be invented, that speeds of 2G were unusable for anything more than plain text, and that no one was capable of building its many components. The iPhone won because it was the right product at the right time and was rooted in the thriving iTunes ecosystem, too.

The history of smartphones allows me to return to how this essay began: the Meta’s Quest line and Amazon’s Alexa devices. If the smartphone category is essentially unassailable, then any company that hopes to have hundreds of millions—let alone billions—of daily hardware-based users needs to bet on a new category. While this eases competitive intensity, it means betting on an idea that might not become popular or commercially viable—and even if it does, you still might be too early or too wrong.

As AI proliferates through every possible app, service, and platform, it’s now clear that Amazon’s aggressive bet on the technology was not wrong, nor was the timing (OpenAI was founded a year after the first Alexa debuted). However, Amazon’s technical approach seems wrong compared to today’s generative models (e.g., large language models). Amazon’s near-exclusive focus on voice as an input and output probably constrained its usage and thus also its training. As Amazon pivots to generative systems and launches image/video/text-based outputs, it’s also possible that the company’s large footprint of Alexa devices will prove to be an asset.

When it comes to XR devices, we’re starting to see echoes of the competing theses of Microsoft and BlackBerry versus those of Android and iOS. Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Google are all launching their platforms at different prices (e.g., Meta at $400–500, Apple and Microsoft at $3,000+), prioritizing different customers (Meta targets everyone, Microsoft is focused on military and industrial applications, Apple on high-end households and designers) with different features and at different times. We don’t yet know what’s “right” in XR, but we can still hypothesize that Meta needs to be more than “right” in its go-to-market approach. Meta needs those that are already operating large-scale hardware ecosystems—most notably, Apple—to be so wrong in timing or, or so long in their initial approach that it takes years to recalibrate, that it could build a defensibly large ecosystem before competition arrived.

It’s here that Zuckerberg’s gambit becomes so tricky. Throughout 2015 and 2016, Mark Zuckerberg repeated his belief that within a decade, “normal-looking” AR glasses might be a part of daily life, replacing the need to bring out a smartphone to take a call, share a photo, or browse the web, even as every big-screen TV would be transformed into a $1 AR app. Yet it turned out that the technology was harder to advance than nearly anyone assumed, and the minimum viable version of an XR device was higher, too. Today, the install base of Meta Quest devices is around 20MM, with actives a fraction of that, and now Apple is coming to market. Certainly, Apple would have arrived earlier if the technology had been simpler, but regardless, the window where you could bet on an XR future others doubted or considered too far away to pursue has largely closed.

Apple’s arrival does not doom Meta’s efforts. As mentioned in the introduction, it’s likely that Apple’s unveiling legitimizes the category (buying Meta more investor support), drives sales of the Meta Quest 3 (consumer support), and leads to more software being made for XR devices (developer support, which is necessary to making the devices worth having in the first place). But beyond Apple’s extraordinary reputation for arriving second (or even later) to a market but being the first to crack it, we have to take stock of the many advantages Apple will bring. For example, Apple’s investments in XR are extraordinary—likely in the tens of billions, just like Meta—but the company doesn’t disclose this information.

What we do know is Apple’s R&D budget. Since 2010, Apple has spent $145B on R&D. In 2022 alone, this sum passed $25B, which was both an extraordinary sum (it exceeds Meta’s 2022 net income and is twice Meta’s 2022 investment in Reality Labs) and a small one (it’s only 7% of Apple’s revenues, though this share has doubled in recent years). Incidentally, Google’s Search-related payments to Apple fund more than 75% of this investment. Another fun trivia point: Apple’s 2021 privacy changes cost Meta $10B in operating cash flow the following year - which represented 63% of Meta’s Reality Labs’ spend!

Given the company’s enormous R&D budget, it should be no surprise Apple’s is also one of the largest patent filers in the world, with 2,300 awarded (and more requested) in the U.S. 2022 alone. That figure outstrips Meta by a factor of 2.3.

There is no way to know how much of Apple’s R&D spend relates to its XR headsets and the company never discloses (and argues it does not have) direct P&Ls for its products. Investments in Apple silicon technology, displays, production capability, et al, are widely repurposable. But when he unveiled the Vision Pro device in June 2023, Apple CEO Tim Cook said the device counts more than 5,000 patents. Reports suggest that development on Vision Pro began in late 2015, meaning 30% of patents awarded to the company since 2018 were for the Vision Pro (presumably this excludes patents-related to the device, but which are not used by it). If one assigns 30% of Apple’s $135B in R&D over this time to the Vision Pro, that’s $41B – roughly inline with Meta’s spend after accounting for M&A, device marketing, and device subsidies. Direct allocation may overstate or understate (the latter is more likely – XR R&D likely exceeds that on say, Macbooks or iPads on a dollar-per-patent basis), but even a 30% haircut results in $27B in spending since 2018. As with Meta, this sum cannot be exclusively attributed to a single device (e.g. the Vision Pro, as it also includes foundational investments for other XR-related devices (e.g. AR glasses versus this MR-focused headset), and subsequent entries to the Vision line.

In a GQ interview in April, Apple CEO Tim Cook tacitly explained why the company’s XR headset took so long to develop and how it might differentiate from Meta’s devices, while also revealing why R&D costs were so high. When considering entering an existing market, he said, he ponders the following issues: “Can we make a significant contribution . . . something that other people are not doing? Can we own the primary technology? I’m not interested in putting together pieces of somebody else’s stuff. Because we want to control the primary technology. Because we know that’s how you innovate.”

Over the past decade, Apple has also made numerous AR/VR/MX/XR acquisitions, buying companies such as Spaces, Camerai, NextVR, Vrvana, SensoMotoric, Emotient, and RealFace.

But among Apple’s many, many advantages, the most important is its ecosystem. There are more than a billion iOS users today, and the average user has a second Apple device; many have several. Apple’s XR device will integrate seamlessly across its iPad, iPhone, Apple Watch, Apple TV, and Mac lines, synchronizing content (e.g., iCloud) and permissions (e.g., entitlements and credentials) and often likely inputs as well (wearing an Apple Watch will likely aid XR-based hand gestures, and many users will want to use their MacBook to present content in XR events or to type while wearing the headset). Bloomberg reports that the device will also run (and connect to) “hundreds of thousands” of existing iOS apps at launch.

This is Meta’s challenge. Next week, the company may find it largely validated in both investment and thesis. Yet it may also turn out that the company launched its XR headsets too early, but also without enough of a head start. If Apple is right to focus on a higher price point ($3,500) than both the Quest 3 ($500) and Quest Pro ($1,500), Meta can respond (make no mistake, the bill of materials matters here—the components cost for Apple’s headset is 4x the retail price point of the Quest 3). But if Apple overshot on specs and pricing, it too can rapidly move downwards.

Time will tell who wins in XR; Apple may “win” in the sense it did with iOS—a distant second place in users, but a distant first in software revenues and total profits—but still leave lots of room for Meta. Android has more than 2.5B users and, as Google has proven, this reach can be used to fortify many, many other markets. For that matter, Android seems to be behind in XR today, but its ecosystem (inclusive of dozens of outside OEMs that build hardware for Google) will allow a rapid catch-up.

Regardless, we can align on a few points. If Meta does “lose” in XR, its failure will probably not stem from spending too much and the consequences will go far beyond direct revenues. If it wins, the spoils are likely to far surpass the losses required to get there.

Post-Script (Written on June 5, by popular request)